In Papua New Guinea (PNG), Tuberculosis (TB) rates are among the highest in the world and TB is the second leading cause of death. If you’re trying to remember where this country lies in relation to the continent of Africa, it’s the island that sits above Australia and is about a third of the way around the world from Africa, or, as Dr Essa Djama says, “Very, very far!”

Essa is an MSF doctor from Somaliland who recently spent 14 months as a medical team leader in this distant part of the world. It was an experience he found extremely interesting for several reasons, not least of which was the fact that it is so far from his home – 10,900 kilometres away to be exact.

Having worked the last seven years in MSF projects in Yemen, Afghanistan, Syria, Somalia and Iraq, the remote setting of the TB response and outreach project at Kerema Hospital in the Gulf province of PNG was a notable change for the doctor. “The project is isolated by rivers, mountains and the ocean, so it was difficult to move around,” he says. “For example, three of our basic treatment units could only be reached with a dinghy boat, or sometimes by helicopter.”

Essa explains that because so many people live in remote areas far from health centres and do not have money for transport, many TB cases go undetected, which is why MSF established the project in this particular region, in collaboration with community leaders, the Gulf Provincial Health Authority, National TB Programme and National Department of Health. But, the project is not as simple as screening and getting people on to treatment. Without an effective follow-up system, many people fail to complete their treatment for TB, putting them at risk of developing a drug-resistant form of the disease, which is more difficult to treat and requires even more tablets in an even longer course of treatment.

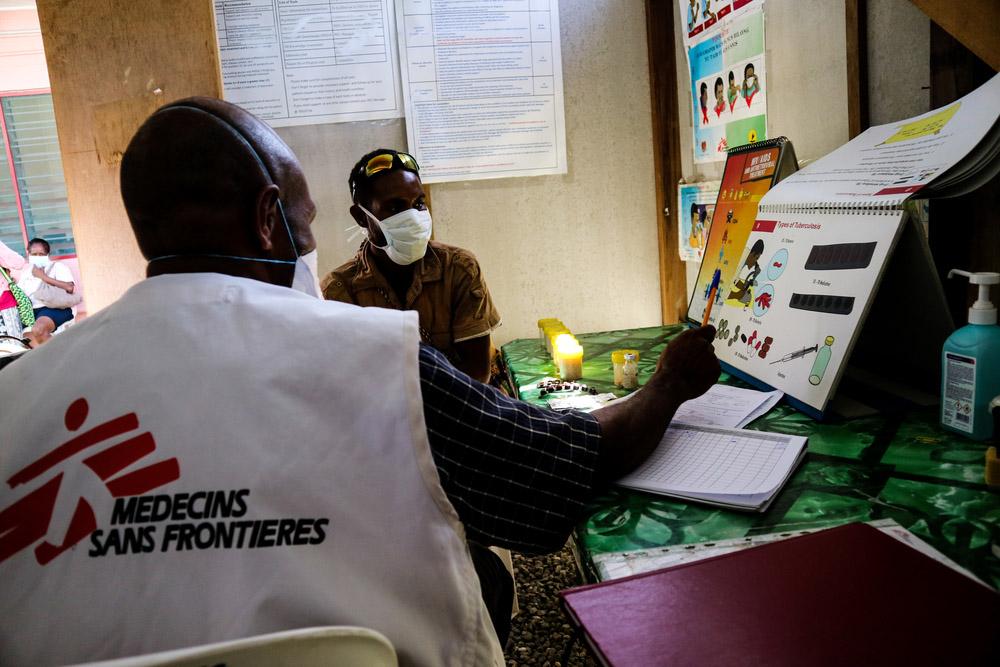

“MSF has several strategies in place to address these barriers, one of which is a decentralised model of care, which basically means that we bring care to the communities, and people do not need to travel to a medical facility as frequently to get treatment and medication,” says Essa. “We go to people’s homes, for example, and we visit several TB clinics once a month in these remote villages and provide screening and medication. Healthcare workers also follow up with people on TB treatment and refill their prescriptions in about 18 sites. They walk or bicycle once a month to do this to make sure treatment programmes are not interrupted.”

These mobile teams also give people information about the disease and offer counselling. “When any individual is diagnosed with TB, we make sure we go to their home to screen family members and anyone else who is close to the people affected by TB. We also check that their living conditions are conducive to recovery and that they have enough drinking water and food,” Essa says.

In order to encourage an environment of acceptance and support of people affected by TB, health workers try to implement a ‘family model’ of care while also involving members of the community. “The family model entails the involvement of the patients’ family members in supporting their treatment. The community health worker might also involve a community leader and ‘treatment supporter’ to be part of the community of care. We also enable ‘self-administered treatment,’ which gives patients autonomy and allows them to take ownership of their recovery.” Essa explains that these are all part of a cost-effective programme that MSF has formulated over the years to manage TB in under-resourced settings like these isolated communities in PNG.

The doctor’s most memorable patient from his assignment highlights just how well this specialised model of care can work. “I will never forget my young friend, Esther. She was just 10 years old when we diagnosed her with TB and put her on a course of treatment that would last 18 months,” he says. “Every single month for those 18 months, Esther and her father had to travel about 450 kilometres and cross four big rivers in a small dinghy to get to us so that we could do a complete examination and monitor her treatment. We would give them food and money for transportation as the journey was so long.

“Esther was so committed to taking her medication; she was the most incredible patient I’ve ever seen. I left before she finished treatment but I called the team of 8 or 9 doctors I was training for an update. They told me that she is about to complete her treatment soon and was crying… Her father was such a support and together they never gave up. I’m used to working in emergencies; I had never experienced anything like this – it was really one of the most interesting projects I’ve ever seen.”

“The family model entails the involvement of the patients’ family members in supporting their treatment. The community health worker might also involve a community leader and ‘treatment supporter’ to be part of the community of care. We also enable ‘self-administered treatment,’ which gives patients autonomy and allows them to take ownership of their recovery.”Dr Essa Djama, MSF Doctor

While Essa will never forget the determination of his young patient, there are countless similar stories he says. “Patient-centered care plays a major role in ensuring adherence to TB treatment as people’s needs and values were respected as we collaborate with them. Empowering people affected by TB motivates them to be adherent and fully recover.”

In collaboration with the community, Gulf Provincial Health Administration, National TB Programme and National Department of Health, MSF supports Kerema General Hospital and two health centres in Gulf province and has scaled up capacity for TB prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment initiation and follow-up.