Tuberculosis (TB) is South Africa’s deadliest infectious disease. Until recently, globally recommended treatment options available to people with Drug Resistant-TB (DR-TB) took up to two years to complete and included up to 14,000 pills and painful daily injections that caused devastating side effects, including deafness, persistent nausea, and psychosis.

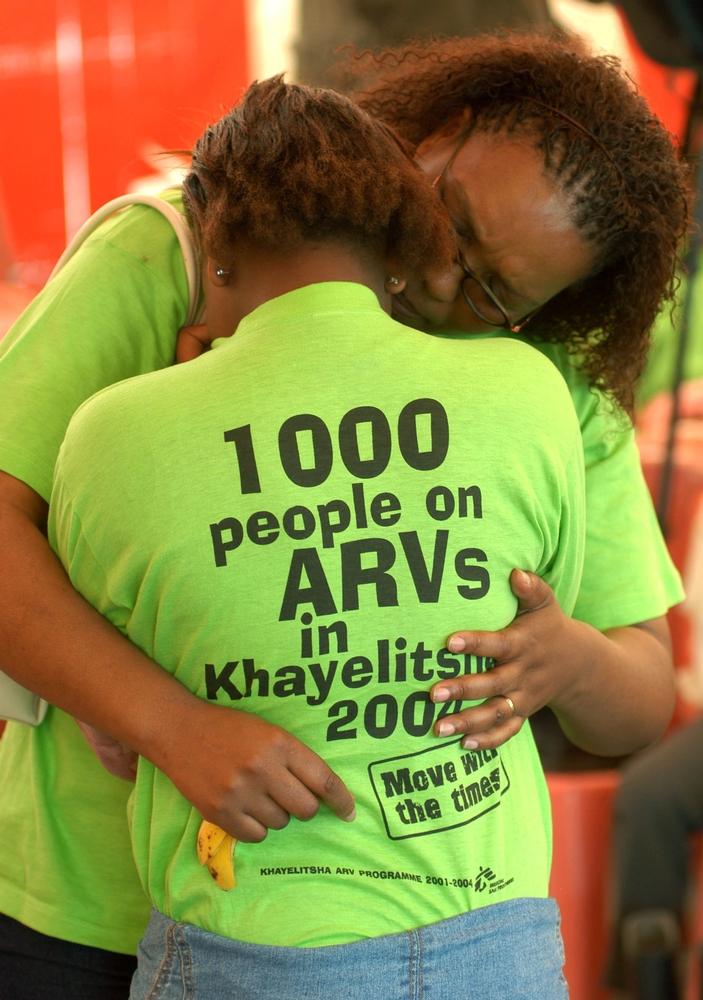

Due to rising numbers of patients with DR-TB, in late 2007, MSF collaborated with local health authorities to pilot a model of care in Khayelitsha that moves management of DR-TB out of overburdened hospitals, and closer to where patients live and work. This community-based patient-centred model of care, enabled clinicians to diagnose and manage stable TB patients at a primary care level throughout treatment, while the smaller proportion of unstable patients were referred for hospital admission.

Early successes of the decentralised model saw increased case detection, strengthened patient support, improved rates of early treatment, decreased time from diagnosis to treatment initiation, improved infection control measures in healthcare facilities, and more effective treatment regimens, as well as cost savings from limiting hospital stays.

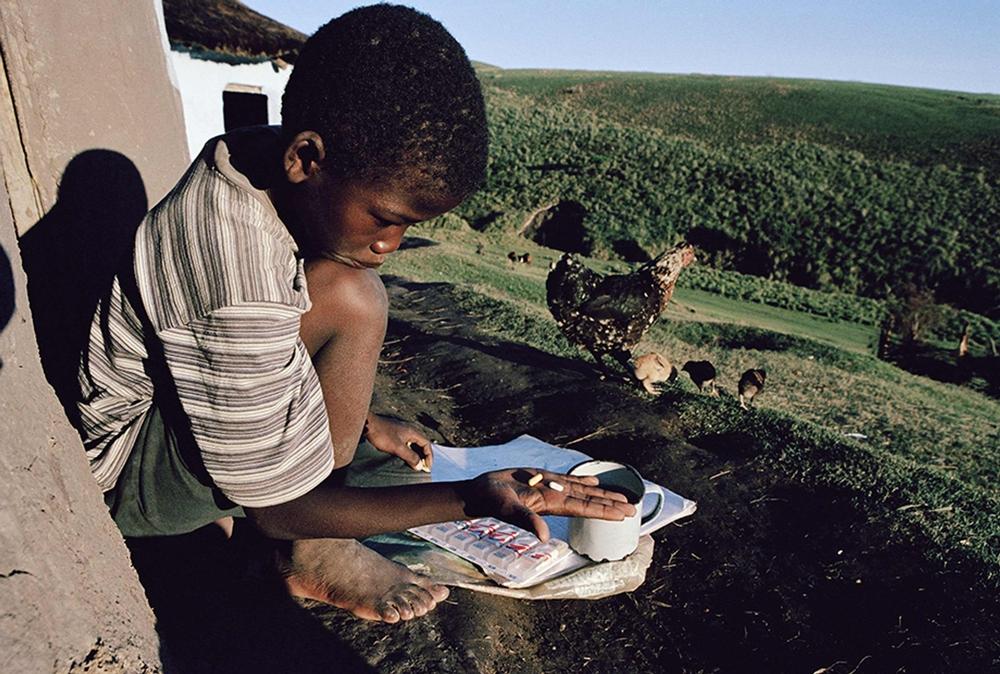

As part of its decentralised DR-TB program, MSF also provides strengthened treatment regimens. However, challenges remain due to the provision of adequate DR-TB patient adherence support and access to shorter, less toxic, and more effective DR-TB treatment regimens. Newer oral DR-TB drugs, such as bedaquiline, linezolid, delamanid and pretomanid, significantly improve DR-TB cure rates and cause fewer side effects than injections, but remain largely inaccessible. Ultimately, orally administered drugs also mean that people can take their medication at home, with even fewer visits to primary healthcare facilities.

In response to clinical research and targeted advocacy efforts from MSF and the Fix The Patent Laws Coalition, including a global campaign by MSF alongside people living with TB in 2019, the pharmaceutical company Johnson&Johnson reduced the price of bedaquiline by nearly a third, to US$1.50 per day, in June 2020.