Kgaladi Mphahlele is MSF’s choice of termination of pregnancy and family planning activities manager in Rustenburg, a city that lies at the base of the Magaliesberg mountain range in the North West Province of South Africa. Kgaladi has been a safe abortion care provider for 12 years and has worked with MSF for three.

In 2015, MSF surveyed 800 women between the ages of 18 and 49 in Rustenburg and found that one in four women had been raped in her lifetime, yet fewer than 5 per cent of those women reported to a health care facility. Since then, MSF has run several sexual and reproductive health programs for the community— including for survivors of sexual and gender based violence— across Bojanala district, where Rustenburg is located, in partnership with local health authorities.

In addition to community outreach and health education in more than 20 schools in the district, MSF supports four Kgomotso Care Centers (KCC) providing sexual violence care.— Kgomotso means “place of comfort” in Setswana, one of the official languages of South Africa, and these care centres provide an essential package of medical, social, and psychological care for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence. MSF also supports the sexual and reproductive health units in two community health centres in Boitekong and Phokeng, where individuals from the area and survivors of sexual and intimate partner violence referred from the KCCs can receive a wide range of services including safe abortion care.

Kgaladi is responsible for the direct provision of safe abortion care, clinical training, and mentoring staff in these health centres, and 13 other facilities across Bojanala accredited by the department of health to provide safe abortion care. Here he talks about the secondary impacts of COVID-19 on access to contraception and safe abortion care — and why sexual and reproductive health services are always essential health care.

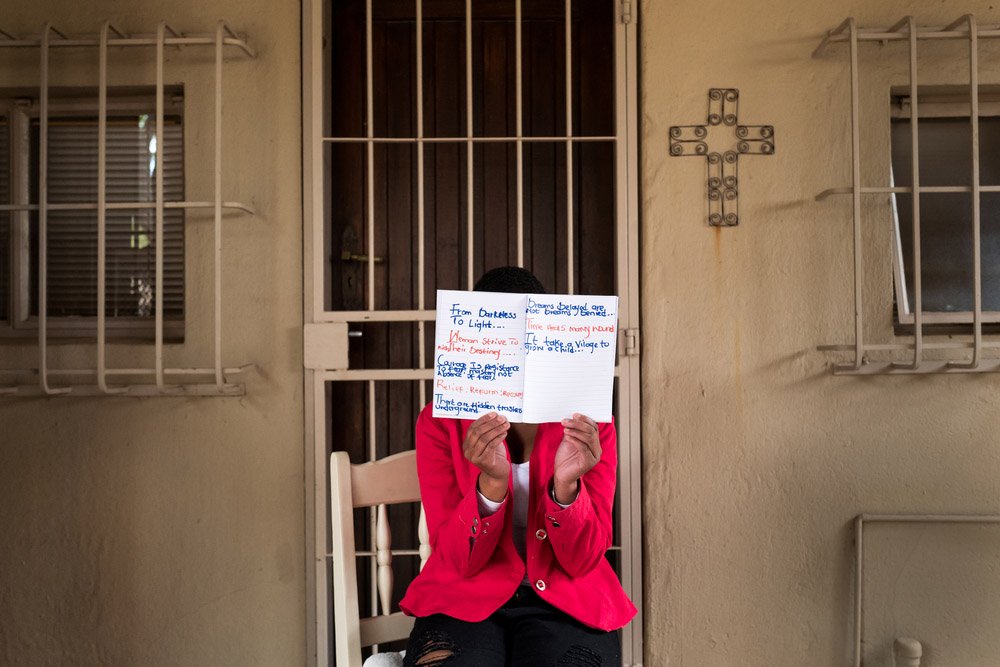

Tshireletso*, a 35-year-old woman, came into the clinic today requesting a termination of pregnancy. Unfortunately, I was unable to help her as she was too far along in her pregnancy. She was 27 weeks pregnant. I asked why she had waited so long to see us. She told me the procedure was initially booked for March 27, but that was the first day of the national COVID-19 lockdown, and she couldn’t get to the clinic for her appointment. She came back to the clinic a week later but was turned away by the security guard working for the Department of Health (DoH), who told her that there were no abortions taking place and she needed to come back when the lockdown was over.

So she came back today, the day lockdown restrictions were reduced to level three. It was her third attempt to get the essential care she needed. She pleaded for me to help as she was not currently working and she had children at home to support. But it was too late, I couldn’t help her. We provided her with counselling and connected her with a social worker, but this is just a really sad example of how restrictions implemented as part of the COVID-19 response have affected women’s access to essential health care services.

In the first four days of the lockdown in South Africa the number of complaints of sexual and gender-based violence lodged through the national hotline tripled, but the number of patients coming to seek care at our KCCs decreased. And it wasn’t just victims of violence who were not seeking care. In April, at the community health centres in Phokeng, 80 per cent fewer women came to seek safe abortion care, and women coming to receive family planning services dropped from 2,000 to 800. Public transport was disrupted and curfews restricted people’s movements. Lockdown restrictions also put many people out of work, so some people could just not afford to travel to a facility. People were calling out for help, but they were not able to leave their houses to get to the clinic.

Defining essential care

The pandemic has hit us all by storm. Nobody was prepared for it. At the beginning of the lockdown, we realized that many facilities had misinterpreted the national guidelines sent by the DoH. As a result, safe abortion care in many facilities was stopped—as it was being designated as an elective procedure, which, according to the guidelines, could not continue. In other cases, it was deprioritized, as nurses were reallocated from the sexual and reproductive health care (SRH) units to COVID-19 projects. Even in one of the KCCs we support, one of the two DoH nurses was reallocated to another department.

MSF decided to make a very clear statement to the DoH, hospitals, and community health centres: Termination of pregnancy is not an elective procedure, sexual and reproductive health care is an essential service, and safe abortion care should be treated as an emergency. We advocated for safe abortion care to continue in the facilities and helped them implement the guidance from the DoH without cutting access to essential services.

Increased need, decreased capacity

We also made other changes to ensure that people could get access to care safely. All facilities are required to screen every patient for COVID-19 symptoms before they can enter. We also screen people to make sure they are only coming for essential and emergency services, otherwise, they have to come back after the lockdown.

But the community health centres we support don’t just offer sexual and reproductive health services. They offer a whole range of primary health care.

To make sure women seeking safe abortion care were not being turned away during the screening process at the facilities we support, we decided to split people into groups before they are screened. We say, “Everyone seeking sexual and reproductive health care, stand on this side.” And those people are prioritized and screened by a health worker instead of a guard. Everyone seeking safe abortion care is seen that same day.

We normally can perform 20 abortions per day, but with the measures put in place to decongest the facility to allow physical distancing—such as reducing wait room capacity from 50 to 15 and increasing space between beds— as well as staffing shortages, we can only provide eight to ten terminations of pregnancy daily. If we have reached capacity for the day, we do the scan and book the patient in for the abortion at a later date, prioritizing those who are further along in their pregnancy. We also offer to pick them up from their homes—a service we also offered before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Seeking care from home

At the beginning of the lockdown, MSF started telehealth counselling, where victims of violence could call into our centres to get help. We’re also working with the DoH to provide the national police hotline with counselling resources, as the hotline is currently only supported by social workers—with no psychological care provided or referral to medical care if needed.

We also plan to start providing telehealth so we can consult with women who are seeking safe abortion care and prescribe abortion medications over the phone. Self-managed abortions are proven to be very safe. We empower the woman to know what to do if the bleeding doesn't stop, or what to do in case of an emergency—but research shows that 99 per cent of abortions with pills are completed without complications.

The main barrier in South Africa is that self-managed abortions can only be done up to nine weeks. We are trying to advocate for the DoH to increase the limit to 12 weeks, as we know it’s a safe procedure and it would greatly help to reduce the number of women who have to be admitted as in-patients to the health care facility. It would also help us address the backlog of patients we have booked in for future dates.

Safe abortion care is healthcare

Termination of pregnancy has been legal in South Africa since 1996, but there is still a lack of providers and a lack of health care professionals who want to become providers. And the few facilities that do provide safe abortion care usually have only one person responsible for the whole unit. Before I became an abortion provider, I was working as a nurse at a health clinic in Mpumalanga, about four hours east of where I work now. We had a patient who came in and was bleeding heavily—I didn’t understand why. We managed to stabilize her and referred her to the hospital for treatment.

That afternoon I went to visit her. She told me that she bought abortion pills off the streets from an illegal provider. When the bleeding wouldn’t stop, she came to the clinic as soon as possible. The following day I asked my manager at the clinic about the woman. “Termination of pregnancy is legal in South Africa,” I said, “So why are people still going to the streets to end their pregnancies?” My manager explained that there were just not enough abortion providers. In Mpumalanga, at that time, no health centre offered safe abortion care.

So I decided to become an abortion provider—and I never turned back. Safe abortion care has always been something that I view as health care—I'm helping people in need. At the end of the day, it is the woman's choice what she wants to do with her body. We need to ensure that women always have access to safe abortion care, especially during a global pandemic.

* Name has been changed to protect the identity of the patient.