Underreported and even ignored, Sudan is facing a monumental humanitarian crisis. A brutal civil war has forced more than 11 million people to flee their homes. Men, women and children are suffering massacres and violent injuries. And, according to the World Food Programme, over 25 million are now facing acute hunger.

Right now, this is the largest displacement crisis on the planet. It's one of the worst seen in decades, yet no one is really talking about it. Sudan rarely makes the headlines, and even aid agencies are barely responding. For over a year, Doctors Without Borders (MSF) has been raising the alarm on this overlooked emergency while our teams work to treat people caught in the middle of it. In some places, we are the only ones there. We owe it to Sudan to speak out.

SUPPORT OUR EFFORTS IN SUDAN

Sudan is a vast and diverse country. It is home to over 48 million people speaking more than 115 languages and dialects in an area equal to France, Germany, Italy and Spain combined.

On Saturday, 15 April 2023, the people of Sudan woke up to a civil war.

Intense gunfights, shelling and airstrikes had erupted around the capital, Khartoum and would soon spread to other cities, especially in the western region known as Darfur.

This conflict didn’t come from nowhere. A military coup in 2021 led to an uneasy political and economic situation. Tensions grew between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) – a group that had previously operated on behalf of the government.

Since those first days, new regional militias have entered the conflict on both sides, with civilians frequently being targeted in acts of extreme violence, often because of their ethnicity.

Healthcare is under direct attack.

Hospitals and healthcare staff have been routinely attacked in Sudan.MSF alone has recorded at least 60 incidents of violence against our people, our vehicles and our buildings. The MSF-supported Al Nao Hospital has been shelled on three separate occasions. At the same time, an airstrike near the Babiker Nahar Paediatric Hospital killed two children in the intensive care unit after the roof collapsed.

In June 2024, the World Health Organization estimated that, at best, only 30 per cent of Sudan's healthcare facilities are still functioning.

Humanitarian aid is being deliberately blocked.

A staggering 25 million people are estimated to need humanitarian assistance in Sudan. From the start of the war, MSF has been working with the Ministry of Health to treat some of the vast numbers of people who require urgent medical care.

However, this hasn’t stopped the Government of Sudan from repeatedly and deliberately obstructing humanitarian aid, especially to areas outside of SAF control. This is the weaponisation of aid, and it is costing lives.

The consequences are clear and dangerous, from blockades preventing emergency supplies from crossing frontlines to denying travel permits for humanitarian workers.

Medical supplies are running out.

The obstruction of humanitarian aid means medical supplies are critically low. At times, this had made some life-saving care almost impossible.

In just one example, the MSF surgical team at Bashair Teaching Hospital in Khartoum had carried out almost 3,000 procedures – including war surgeries and emergency caesarean sections – when they were forced to suspend operations for more than three months as a military blockade exhausted their supplies.

Elsewhere, in RSF-controlled areas where different militias operate, healthcare facilities and warehouses have been regularly looted, leaving medical teams without essential medicines and equipment.

There is a catastrophic food crisis.

The conflict has disrupted food supply across Sudan, and people have been cut off from their jobs, meaning millions now face a new crisis: hunger.

At Zamzam – a vast camp in North Darfur where over 300,000 people are sheltering – our teams have witnessed the severe impact of this food insecurity.

In March and April, MSF found that almost a third of children here were suffering from malnutrition, as well as a third of pregnant and breastfeeding women. This is double the ‘threshold’ rate considered an emergency for both groups. In response, we established a field hospital to provide urgent care.

However, we now fear the situation has deteriorated even further since a surge in heavy fighting began in May, around the nearby city of El Fasher.

Streams of people have fled towards the camp, and it’s not known how many have arrived. Access to food has become even more challenging, and MSF staff have been displaced. This makes it extremely difficult to understand what is unfolding inside Zamzam accurately. However, it is likely to be alarming.

The crisis has spread.

The crisis is not confined to Sudan. Millions of people have made the desperate decision to seek safety in neighbouring countries and become refugees.

In West Darfur, extreme violence in the city of El Geneina has driven an exodus of people over the nearby border with Chad, where hundreds of thousands are now living in makeshift camps.

In response, MSF deployed a state-of-the-art inflatable hospital to help treat the war-wounded men, women and children arriving at Adre, a small town on the Chadian side of the border. In the conflict's early months, we saw 15,000 arrivals in just four days. Over 900 were wounded.

However, with so few humanitarian organisations working in the area, the needs across the many camps are still shockingly high, and the flow of new arrivals has been constant, forcing people to survive with scant supplies of food, water and shelter.

The UN reports that more than 600,000 people have fled to Chad. Around 730,000 people have also arrived at camps in South Sudan, where our teams are reporting a spike in malnutrition.

Civilians are being targeted.

As the first refugees crossed the Chadian border, the MSF team at Adre treated hundreds of people – including children – for gunshot wounds in the back, buttocks and head. They had been shot while running away.

This was just a hint of what was taking place inside Darfur.

An MSF team has since collected testimonies from more than 1,500 people across three refugee camps. Many shared how they had been attacked due to their Masalit ethnicity, with men being systematically targeted.

The accounts paint a picture of violence, looting, the burning of homes, sexual violence and massacres, rooted in political and economic rivalries along ethnic lines.

Almost 20 years after the war in Darfur and a campaign of ethnic cleansing, there are now dangerous echoes in this new crisis. MSF has shared our evidence at the highest levels and will continue to raise the alarm about the situation in front of us.

Sudan has been abandoned.

In the middle of devastating violence and suffering, millions of people have been abandoned. Including by the UN. In hard-hit areas of Sudan like Darfur, Khartoum, and Al Jazirah, MSF is one of just a few international organisations still running hospitals and healthcare. In some places, we are the only ones there. MSF has called the situation “a humanitarian void”.

This emergency is far more significant than our capacity to respond. We cannot do it alone. Many international organisations were present in Sudan before the war, but they left and have failed to return. At the same time, Sudanese authorities have imposed increasing restrictions.

MSF has repeatedly called on the UN to step up. The UN and its partners have held conferences – most recently in Paris on 15 April, the first anniversary of the crisis – but have failed to deliver on plans.

The organisation has self-imposed restrictions on accessing parts of Sudan and has not intervened in crucial opportunities that could have opened up humanitarian access.

MSF calls on the UN to be bold in the face of an enormous crisis, focus on precise results, and actively contribute to the massively scaled-up humanitarian response that is urgently needed. Sudan requires action.

Sudan crisis FAQ

For more than a year, large parts of Sudan have been experiencing ongoing violence, including intense urban warfare, gunfire, shelling, and airstrikes. The health system, already fragile before the conflict started, is struggling to cope with existing and emerging medical needs while facing overwhelming pressure from the destruction and looting of health facilities, acute shortages of utilities and medical supplies, and under-resourced, unpaid, and overworked personnel. As a result, people face significant challenges accessing medical care throughout the country.

Ethnic violence

The violence has taken on an ethnic dimension in Sudan’s Darfur region, which was devastated by another war in the early 2000s. Refugees who have fled from West Darfur to Chad describe an unbearable spiral of violence, with looting, homes burned, beatings, sexual violence, and massacres, particularly targeting the Masalit ethnic minority.

Displacement

Sudan is experiencing the world’s largest and fastest-growing internal displacement crisis. More than 10 million people—1 in 5 people in the country--are currently internally displaced and over 2 million have crossed the borders to neighboring countries. MSF is providing assistance for Sudanese refugees and returnees in South Sudan and Chad. Half of the internally displaced people are from Darfur, a key hotspot of violence, and a third come from Khartoum, a city that has lost about half its original population of 8 million. Before the start of the current war, Sudan already had over 2 million internally displaced people.

Many displaced people are sheltering in crowded camps established in the aftermath of the 2003 Darfur crisis, with no roof over their head to protect them from rain and the scorching summer heat.

Insufficient humanitarian response

MSF is currently one of the few international organizations working in parts of Sudan that are more heavily impacted by the violence. The UN and other humanitarian organizations are barely visible on the ground beyond the main entry points in the east (Port Sudan) and west (El Geneina). This is partly due to the mounting violence, lawlessness, and access challenges imposed by both parties to the conflict.

Food insecurity and malnutrition

Food insecurity and malnutrition have reached catastrophic levels in parts of Sudan. In March and April 2024, MSF conducted a mass screening of more than 63,000 children under 5 years old, as well as pregnant and breastfeeding women and found a catastrophic and deadly malnutrition crisis in Zamzam camp, North Darfur. Of more than 46,000 children screened, 30 per cent were found to have acute malnutrition, including 8 per cent with severe acute malnutrition. Similar figures were found among more than 16,000 pregnant and breastfeeding women who were screened: a third were acutely malnourished, including 10 per cent with severe acute malnutrition.

Malnutrition will increase even further over the coming months amid the ongoing lean season, and as the rainy season begins, transporting vital supplies will be more challenging.

The UN and other organizations have warned that Sudan could turn into the world’s largest food crisis, and project that a famine could take place in the coming months if there is no immediate scale-up in food delivery and unimpeded access to people in need of aid.

Access to healthcare

Sudan’s health system was already fragile before this conflict.. Today, artillery attacks, the occupation of hospitals by armed forces, power outages, and shortages of medical supplies and personnel have brought Sudan’s health system to the brink of collapse. In hard-to-reach areas and areas heavily affected by the war, like Khartoum and Darfur, only 20 to 30 percent of health facilities remain functional, and even so, at a minimal level, according to WHO. Active fighting and lack of transportation hinder patients’ ability to reach the functioning health facilities. By the time many arrive at a hospital, they are in critical condition; pregnant women often have to give birth at home.

Despite our best efforts, MSF has been forced to close projects that provided critical care in three states due to insecurity and attacks on healthcare workers and facilities.

Disease outbreaks

Before the current war, Sudan had a high prevalence of non-communicable diseases and faced both seasonal and non-seasonal outbreaks of diseases like measles and cholera. As the ongoing conflict has disrupted essential services such as water supply and the availability of medicine, the health situation has become even more dire.

As people flee to overcrowded camps, the risks of disease outbreaks have risen, especially among children. People with chronic diseases such as diabetes, asthma, and heart disease are facing severe complications due to a lack of medicines and lack of access to functional health facilities.

Access to vaccination

Lack of availability and access to vaccinations has left many children unvaccinated, creating a high risk of outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles.

Surgery and emergency care

The war has put intense pressure on hospitals with surgery and emergency departments. MSF teams are seeing war-wounded patients with catastrophic injuries caused by explosions, bullets, and stabbings, and are responding to mass casualty incidents. People injured in road traffic accidents and women in need of emergency cesarean sections also face difficulty accessing care.

Maternal and pediatric care

Pregnant women and children residing in camps, particularly in the western, southern, and eastern regions of the country, are especially vulnerable to health risks due to harsh living conditions and the insufficient humanitarian response. Women often give birth in unsanitary tents or at home, increasing the risk of complications and infections, while access to prenatal care remains insufficient.

At the same time, the need for postnatal and pediatric care is immense. Children under 5 years old, especially newborns and toddlers, have an increased likelihood of contracting diseases and are more vulnerable to complications from malnutrition, malaria, measles, or acute watery diarrhoea.

Obstruction of humanitarian access

Throughout the war, but particularly in the last six months, there has been a systematic obstruction of aid, humanitarian access, and supplies. It has been difficult to get visas for humanitarian staff to enter the country and travel permits to move around Sudan. Permits to cross the front lines, for example, from Port Sudan to RSF-controlled areas, have been repeatedly denied. Attempts have also been made to prevent aid from entering the country across the border, including from Chad and South Sudan.

Mental health

The war and violence continue to have serious mental health implications for people fleeing or stuck in the midst of the fighting. People continue to experience extreme trauma as they lose family members and loved ones, witness and experience violence, including sexual violence, and the deterioration of their own health or the health of loved ones. Many continue to fear for their lives with the continuous heavy fighting, especially in Khartoum, Darfur, and Al Jazirah states.

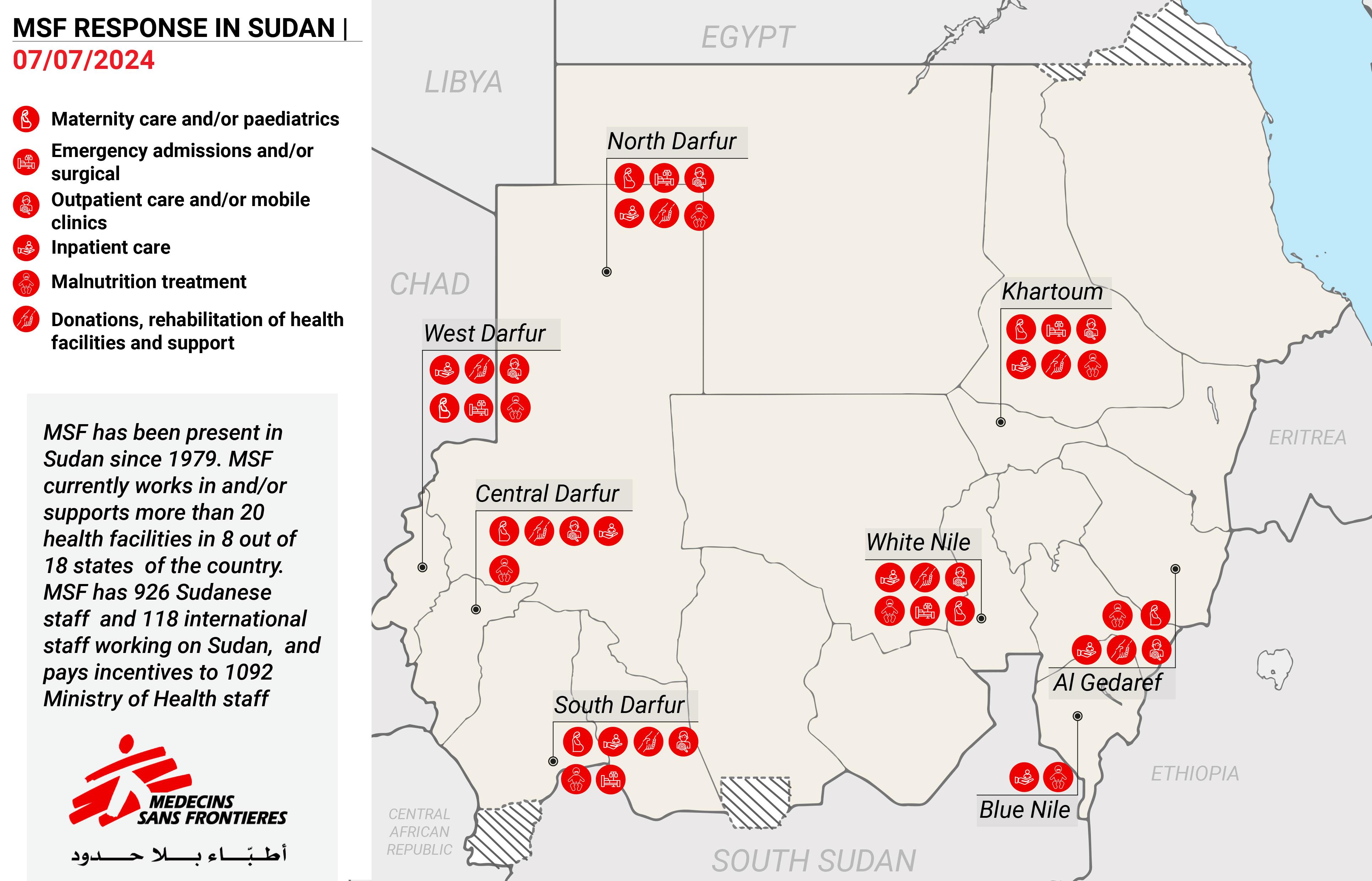

MSF currently works in eight states across Sudan, supporting 14 hospitals and seven primary health care facilities and clinics, and running mobile clinics in two camps. We work with a team of over 1,000 staff, including over 900 Sudanese staff, providing emergency treatment; surgical care; mobile clinics for displaced people; treatment for communicable and non-communicable diseases; maternal and pediatric health care, including safe deliveries; vaccinations; water and sanitation services; and donations of medicines and medical supplies to health care facilities. We also provide incentive pay, training, and logistical support to Ministry of Health staff, and continue some of our medical activities that were in place before the start of the war.

Khartoum

MSF has been working at Bashair Teaching Hospital alongside volunteers and Ministry of Health staff since May 2023. The hospital has an emergency department and provides surgical and maternal care including cesarean sections.

Zalingei Teaching Hospital entrance, Zalingei, Central Darfur state, Sudan.

Zalingei's teaching hospital has been looted and attacked multiple times. Sudan 2024 © Juan Carlos Tomasi/MSF

Central Darfur

Zalingei Teaching Hospital, one of the sole secondary healthcare facilities for Central Darfur, has been looted and attacked multiple times over the past year. Since early April 2024, MSF has re-opened and rehabilitated the maternity department, emergency room, inpatient therapeutic feeding centre, and pediatric department. The rehabilitation of the surgical department is ongoing.

White Nile

In the early months of the war, White Nile state saw the arrival of tens of thousands of people fleeing other areas of Sudan, most from Khartoum. Many were South Sudanese and took shelter across existing refugee camps; others were in transit toward South Sudan. To support them, as well as internally displaced people, MSF launched a response in June 2023. Today, our teams are still present in Al Alagaya and Um Sangoor camps, where we support two primary health care centres, providing services such as outpatient consultations, outpatient therapeutic feeding centres, mental health support, and sexual and reproductive health care activities.

MSF also supports Al Kashafa Hospital, with a focus on its inpatient therapeutic feeding centre, maternity and paediatrics, and emergency room. Precariousness and increased overcrowding led to a spike in diseases in the camps in 2023 since many children were not vaccinated, with a measles outbreak coinciding with high malnutrition rates. MSF supported the Ministry of Health in mass vaccination from August to November; medical indicators subsequently improved, and we were able to control the outbreak.

Blue Nile

At Ad-Damazine Teaching Hospital, MSF operates a nutrition ward with a bed capacity of about 120. The ward provides crucial hospitalization services for severely malnourished children, particularly for complicated cases where children cannot be treated at home. Currently, an average of about 70 children are admitted per day.

Gedaref

MSF has been a vital health care provider in Tanideba camp since 2021, offering secondary and emergency health care to both the refugee and host communities. The camp’s hospital provides a range of services, including primary and mental health care, pre- and postnatal care, family planning, nutrition, emergency stabilization, and referrals. It has a 24/7 emergency room, an inpatient department, and a Kala Azar diagnosis and case management unit. The maternity department provides deliveries and basic emergency obstetric and neonatal care, including care for survivors of sexual violence, and referrals of complicated cases and life-threatening emergencies. The project also includes community engagement, health promotion, disease surveillance, outbreak monitoring and response, and water and sanitation activities.

In Um Rakuba camp, MSF ensures access to preventive and curative health care for Tigrayan refugees from Ethiopia as well as surrounding communities. The MSF health facility provides a wide range of services, including outpatient consultations, inpatient care, emergency room and maternity admissions, prenatal and mental health consultations, deliveries, and an inpatient therapeutic feeding centre for malnourished patients. MSF also engages in health promotion activities at the hospital, camp, and community level.

MSF currently works in eight states across Sudan, supporting 14 hospitals and seven primary health care facilities and clinics, and running mobile clinics in two camps. We work with a team of over 1,000 staff, including over 900 Sudanese staff, providing emergency treatment; surgical care; mobile clinics for displaced people; treatment for communicable and non-communicable diseases; maternal and pediatric health care, including safe deliveries; vaccinations; water and sanitation services; and donations of medicines and medical supplies to health care facilities. We also provide incentive pay, training, and logistical support to Ministry of Health staff, and continue some of our medical activities that were in place before the start of the war.

South Darfur

Since 2021, MSF has been operating two clinics in the Jebel Marra mountains, Kalokitting and Torun Tonga. These clinics provide primary health care services, including deliveries, nutrition, and referrals to Kass Hospital when feasible. These clinics are the only health care services available in the area. Our work also includes community engagement, health promotion, disease surveillance, outbreak monitoring and response, and water and sanitation activities.

North Darfur

In North Darfur state, hospitals have closed one by one as the fighting has intensified and health facilities have come under attack. Only one major hospital in the city remains open at present.

At the start of the war, MSF ran the maternity unit at South Hospital in El Fasher and quickly reoriented activities to support war-wounded patients when other hospitals in the city became non-functional due to the fighting. South Hospital then became the main referral hospital for the whole of North Darfur state, providing vital services until it was raided and looted by armed men in June 2024 and became non-functional. This was the fifth time it was attacked.

All services provided at South Hospital, apart from maternity, were transferred to Saudi Hospital, where MSF continues to provide support. This hospital has been attacked three times since May 10, and it is the only functional hospital in El Fasher.

MSF also supported the Babiker Nahar Pediatric Hospital after children were evacuated from the original pediatric hospital in April 2023, when the war began, and it was looted. However, this hospital became non-functional on May 11 when an airstrike that landed 50 meters from the facility caused the roof of the ICU to collapse and killed three people, including two children. The hospital had to close due to additional damage. Currently, the children are being cared for in a small facility called Sayed Al Shuhada.

Our maternity department at South Hospital was transferred to Zamzam camp, where we had scaled up our presence following the rapid assessment and mass screening carried out early in 2024 that found a catastrophic malnutrition crisis there. We currently run a field hospital as well as two health clinics in Zamzam. However, due to a reduction in staff and ensuing access impediments (namely the lack of visas to enter Darfur and challenges transporting supplies) it has not yet been possible to increase our activities further.

West Darfur

MSF supports El Geneina Teaching Hospital in the provision of primary and secondary health care services. Our support is focused on pediatric services, including the pediatric outpatient department and inpatient therapeutic feeding centre. MSF also supports the hospital's blood bank, laboratory, sterilization, water, sanitation, and energy.

Chad

Since the war broke out last year, an estimated 682,000 refugees and returnees have crossed the border to Chad. Refugees and returnees from Sudan are now living in multiple camps in Chad and face difficulties securing even the most basic needs. MSF teams are responding in five locations in eastern Chad: Adré, Ourang, Metche, Alachua, Daguessa, Andressa, and Goz-Aschiye, Kimiti province.

In June 2023, more than 850 war-wounded Sudanese, mainly with bullet wounds, were received in the MSF-supported hospital in Adré in the space of just three days. Hundreds of thousands of people previously trapped in West Darfur joined them en masse from June onwards. We heard horrific stories of violence from survivors, including sexual violence. We conducted a retrospective mortality study in refugee camps asking families about relatives who have died, finding that refugees from West Darfur’s capital, El Geneina, were particularly affected, with a mortality rate 20 times higher compared to before the conflict began.

In the camps of eastern Chad, there is currently an outbreak of hepatitis E, which has been exacerbated by poor sanitation and a desperate shortage of clean water in the camps. In Adré camp, there is just one latrine for 677 people, while in Metché camp, there is one latrine for 225 people. Without swift action to improve sanitation infrastructure and enhance people’s access to clean water, there is a risk of a surge in preventable diseases and unnecessary loss of life.

MSF is currently providing more than 70 percent of the drinking water available in Adré, Aboutengue, Metché, and Al-Acha camps. Despite this, people are receiving just 11 litres of clean water per day—well below the 20 litres per person per day recommended for emergency settings. Despite our efforts, the humanitarian response in eastern Chad has been hampered by insufficient funding for humanitarian organizations on the ground, leaving critical gaps in the provision of food, water, and sanitation.

South Sudan

Since the beginning of the war in Sudan, over 740,000 people have crossed into South Sudan to seek refuge. The majority are South Sudanese returnees—people who had previously fled to Sudan during the civil war in South Sudan, which ended in 2018.

The influx of displaced people has further stretched an already overwhelmed system. In the transit centres, the situation is getting worse with increasing food insecurity and health issues, including severe malaria cases, eye infections, acute bloody diarrhoea, and the risk of cholera. There is a lack of funding for water, sanitation and hygiene programs across South Sudan, which is particularly concerning as acute watery diarrhoea is top comorbidity among acutely malnourished children under 5 years old admitted to MSF facilities and as cholera outbreaks have been reported in Sudan.

MSF is responding to the refugee crisis in Renk and Bulukat in Upper Nile state. MSF’s Abyei project is also impacted, with a largely under-estimated 17,404 returnees who have arrived through the Amiet point of entry.

MSF has been present in Sudan since 1979, witnessing historic changes and escalating needs in response to the rapid shifts in the country’s political and social dynamics, which in turn impact health needs.

Our intervention began shortly before the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005), which was fought primarily between the north and south of Sudan and was one of Africa's longest civil wars. MSF was actively involved in providing medical care to war-affected communities dealing with massive displacement, famine, and the outbreak of diseases. With the independence of South Sudan in 2011, MSF continued operations in both countries, adapting to the shifting dynamics of conflict and the division of resources.

When the war broke out in April 2023, many activities were either stopped or shifted to respond to the emerging needs and emergencies across the country. Some activities continued—in Darfur, for example—thanks to the efforts of our locally hired MSF staff, who continued to work despite the extremely difficult personal and environmental circumstances.

MSF provides medical care to anyone who needs it, regardless of race, religion, or political affiliation. We are calling on all parties to the conflict to ensure the safety of civilians, medical facilities, and personnel. Hospitals must remain a sanctuary for people seeking care.

To facilitate our humanitarian and medical work, we speak to all parties to the conflict to request safe, rapid, and unimpeded access to civilians who require medical care and to ensure the safety and security of our staff. This is why our independence and impartiality are essential to our work in all the places we operate worldwide.