Hannah Efrat Voltmer worked with Doctors Without Borders (MSF) as a midwife in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In the city of Kananga, she and her team provided care to survivors of sexual violence and implemented the decentralization of health care in the surrounding communities.

It's just before 8 a.m. at our clinic in Kananga, Democratic Republic of Congo. And we're dancing. Magic System, Cesaria Evora and Maciré Sylla can be heard in the hallways. Our bodies move, full of emotion. Four or five songs, then it's 8:15, and work begins.

Here we provide medical, psychological and social assistance to survivors of sexual violence and people of all ages and genders. The music and dance in the morning are a way for the team to create cohesion and strength because we know that we all have a full day ahead of us that will challenge us emotionally and psychologically.

Violence is omnipresent

In treatment room 1, a healthcare worker treats a woman in her early fifties. She reports that she was stopped on the road by several men armed with a machete and sexually assaulted. The money and crops she was carrying to sell were stolen from her. Her clothes are torn in several places. Her wounds are now being treated, and she is receiving fresh clothing as well as medication. Treatment room 2 is also already occupied – a seven-year-old boy is being cared for by a midwife. He was sexually abused by his teacher.

Sexual violence is often experienced in private spaces such as one's own home or the perpetrator's home. It is not uncommon for survivors to report multiple perpetrators. However, sexual assaults also often occur in public spaces, where people live their daily lives - at the market, on the road, at school, in the field, in the bush, in displaced persons' camps or when they flee.Hannah Efrath Voltmer, MSF Midwife in DRC

Medical assistance within 72 hours

Nearly two-thirds of survivors of sexual violence do not reach our medical assistance until well after the 72-hour window, which is extremely important for preventing infections and unwanted pregnancies, for example. It is not uncommon for survivors of sexual violence to come to us months later, for example, when they are looking for a safe abortion. For children, the reason for the delay in seeking help is often fear. They are also afraid of the consequences of telling their own parents about what they have experienced.

Taking 'the help' to the people

Male survivors also often mention pride as a reason for delaying looking for care after a sexual assault. Societal norms and values shape society's image of masculinity and the role of men. We see in our project data that we are reaching significantly fewer male survivors with our medical care, even though we know there is a great need.

Another barrier is the distance some people must travel to reach our clinic. So, Doctors Without Borders has taken an important step to bridge that barrier by decentralizing care: taking it out into the communities.Hannah Efrat Voltmer, MSF Midwife in DRC

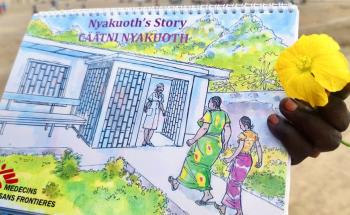

That morning, my colleagues Hélène and Gaston (both nurses) and I go to the office on the second floor, where our health promotion team is discussing the daily program. Later, they will visit several communities in the surrounding villages and hold engaging information sessions about sexual violence with the help of music, loudspeakers and support materials.

One of the most critical pieces of information is where the nearest free medical assistance is. The next thing is the required 72-hour window for receiving HIV post-exposure prophylaxis. Our teams also provide information about the treatment for sexually transmitted diseases and various contraceptive methods.

Fighting the taboo with word of mouth

Since 2017, MSF has provided medical and psychological care to more than 14,000 survivors of sexual violence here in Kananga. Family planning and medically safe abortion are also important components of our work.

Young and adult women learn about our help through word of mouth. The reality in the Democratic Republic of Congo is that unwanted pregnancies are still terminated by unsafe abortions, and many women suffer serious complications or even lose their lives.

Everyone in my team knows at least one woman who has died from unsafe abortion. Among ourselves, we talk openly about it. But otherwise, it's a taboo subject.

Sexual Violence is an alarming part of the everyday life

We know we're only reaching the tip of the iceberg. For so many people here, barriers exist that put adequate medical care out of reach. Sexualized violence is taboo, yet it is part of everyday life for an alarming number of people, even in their own intimate relationships. Child protection is practically non-existent.

I wonder how long it will take until human rights (i.e. protection from violence) are no longer violated.

Everyday life in this project feels very intense and challenging. But powerful and wonderful moments also happen here. We recently baked waffles in the late afternoon in the clinic, listened to music, and sang. Everyone stirred the batter at one time or another, and the waffles were served hot. Alongside all the work we do with our patients, these moments as a team are also vitally important.

It’s at these times that we are no longer health care workers, midwives, psychologists or doctors.... we are simply together as we are.