Dr Gilles Van Cutsem, Senior HIV & TB Adviser for MSF’s Southern African Medical Unit, reflects on the lessons South Africa, and other nations, can take from the first two “waves” of COVID-19 infection to hit South Africa.

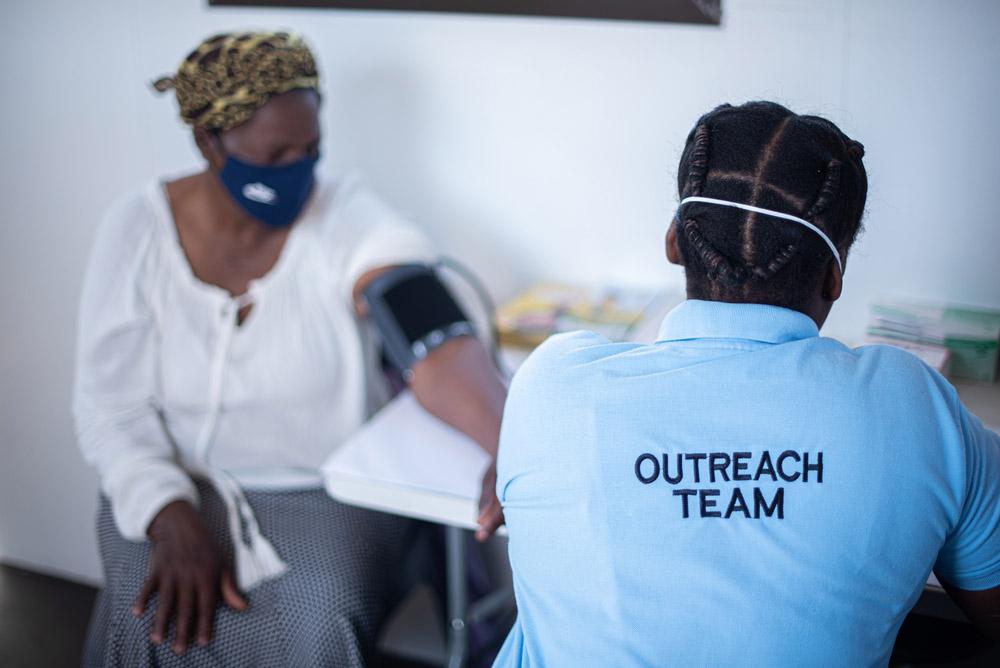

He has supported various MSF activities on COVID-19 in South Africa and recently coordinated the emergency support to Ngwelezana Hospital in KwaZulu-Natal during the second wave. While vaccination, especially for healthcare workers and high-risk groups, is a matter of national and international concern, there are small, low-cost high-impact strategies hospitals can put in place to prepare for future surges in COVID-19 infections.

South Africa was widely praised for successfully flattening the curve of the first wave of COVID-19. Early, strict lockdown measures, including a ban on alcohol, allowed the health system to prepare for a surge of cases. When the first wave eventually hit, the number of cases was lower than expected. Hospitals and clinics had set up screening and triage of patients, additional oxygen, human resource and bed capacity had been created — even if sometimes wastefully— guidelines were in place and emergency departments weren’t overloaded with victims of alcohol-related violence and car accidents.

After COVID-19 was introduced to South Africa, the epidemic spread gradually from within and among provinces which allowed for lessons learnt in one province to be applied in others. By early October 2020, new cases per day were dropping in every province. The first wave ended. Lockdown measures were lifted. People rejoiced and celebrated their newfound freedom.

However, as the festive season holidays approached in December, an extremely dangerous development went unnoticed. The different strains of the virus responsible for the first wave were all rapidly being replaced by one new dominant strain dubbed 501Y.V2, first identified in patients in the Eastern Cape province. This new variant is twice as transmissible as the previous strains. It might also escape our immune system better and be more likely to cause reinfections.

With the increased mobility of people, a sharp drop in prevention measures and end-of-year festivities taking place, the new variant quickly spread in the Eastern Cape through local transmission, then the Western Cape, and a little later Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal provinces and the rest of South Africa.

The number of cases and deaths in the second wave was much higher than in the first. On 8 February 2021, the total number of reported cases in South Africa was close to 1.5 million. The total number of deaths was 43,768. During the months from October 2020 to February 2021, there had been close to 800,000 new cases and an additional 26,000 reported deaths: a 17% increase in cases and a 57% increase in deaths compared with the first eight months of the epidemic. What happened?

The higher transmissibility of the virus and the lower prevention measures of the population created the perfect environment for massive transmission. As many more people became infected, more people were severely ill, more people needed hospitalisation, and more died. As hospitals were overwhelmed by large numbers of patients, the in-hospital death rate increased.

While it can’t be completely ruled out that the new variant causes more severe disease, preliminary data does not indicate that this is the case. What is more likely is that patient numbers exceeded the capacity of the health system. The numbers of doctors, nurses and oxygen points just weren’t enough.

From my personal experience and that of my colleagues in several hospital support interventions MSF undertook in KwaZulu-Natal, hospital staff were so overwhelmed during the peak of the second wave that many patients died because of lack of the basics: oxygen, water, and basic patient monitoring and support.

Small things are crucial

It is in times of emergency that we rediscover the importance of small things. People died because no one noticed that their oxygen mask wasn’t well-positioned any more or that their oxygen saturation was dropping. People died because they didn’t receive enough water. People died because they disconnected from oxygen when trying to go to the bathroom because no one helped them with a bedpan. People died at night when exhausted staff was even less present and alert. People died because of organisational chaos compounded by the rapid addition of inexperienced health staff.

In a normal environment, many of those basic tasks are partially taken over by the patient’s family. In COVID-19 wards, however, the family is not allowed to enter, to prevent further transmission. All these tasks usually performed by family fall on to the nurses. Yet nurses were understaffed to cope with the second wave and finding additional nurses is difficult, sometimes impossible.

These are the lessons we learned, and we’re ready to share

First, there is oxygen. Without it, patients with severe COVID-19 can’t survive. Now is the time to ensure every hospital has sufficient oxygen capacity to deal with the oncoming waves of COVID-19.

Piped oxygen is the best option, but not always feasible. Oxygen concentrators, extracting oxygen from ambient air, are an excellent solution where providing piped oxygen is not possible. The last option is oxygen bottles. They are impractical as they run out quickly and are heavy to move. In addition to oxygen, or in the absence thereof, proning of patients on their stomachs can increase oxygen saturation by 10%. This can be life-saving.

The second essential is sufficient staff for basic patient care.

This can be achieved by task-shifting to entry-level health staff: enrolled nursing auxiliaries, nursing assistants, caregivers, nurse aids or even volunteers. Identifying and hiring a sufficient number of this essential cadre can decrease the burden on nurses and save lives.

If entry-level staff members are ensuring mask monitoring, oxygen saturation monitoring, drinking, feeding, washing and bedpan support, this leaves time for nurses to focus on more medical tasks. Volunteers can be hired to function as runners and porters and to communicate with families.

Emergency response requires a great deal of coordination.

For a team of sometimes inexperienced and/or new staff to work coherently, it is critical to ensure adequate management staff. In Ngwelezana Hospital in Empangeni, KwaZulu-Natal, the addition of a nurse activity manager made an incredible difference to the organisation of the ward, management, training and mentoring of nurses. The same is necessary for entry-level staff.

Do not neglect the night shift.

Most patients die at night. Ensuring increased attention to and sufficient staff for patient monitoring and support can save lives. And make sure basic items such as water bottles, cups, straws, pillows for proning and bedpans are available in sufficient quantities.

These items may be less sexy than ventilators, but they probably save more lives. The number of cases in the second wave declined everywhere after South Africa implemented new prevention measures: a total alcohol ban, curfew at 9pm, prohibition of gatherings. However, this was only put in place after hundreds of people had died. The decline also suggests that the risk for new waves to emerge is high after prevention measures are eased.

The time to prepare for the next wave of COVID-19 infections is now

In South Africa, we’ve learnt a lot from the two first waves and from the fight against other epidemics such as HIV and Ebola. We should not be caught off guard. Many things that can be done now in every hospital. More waves will continue to come as long as there is no equitable access to effective and affordable vaccines that work well against the new COVID-19 variants. This is a priority for the national government and the international community. There is no place for vaccine nationalism in a pandemic.

A relatively high level of prevention measures is likely to be needed to delay and/or decrease future waves. Provincial governments and hospitals can reduce mortality by adequately planning sufficient oxygen capacity, human resources and supplies.

Low-cost high-impact strategies include task-shifting basic patient support to enrolled nursing auxiliaries, and other tasks to lay staff; being prepared to hire sufficient numbers of these cadres; and procuring basic supplies such as water bottles, cups, straws, finger oxygen saturation monitors, pillows and bedpans.

Sometimes the seemingly small things are those that matter most.