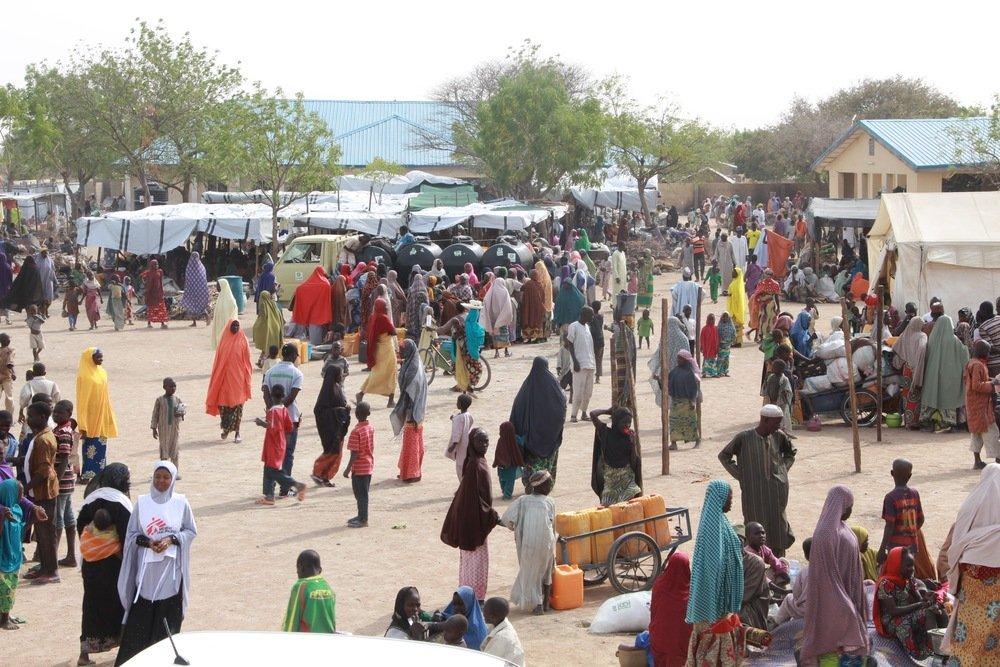

In northeast Nigeria, ongoing conflict and the deadly combination of malnutrition, measles and malaria has claimed thousands of lives. Doctors Without Borders (MSF), which runs 10 medical facilities in six towns in Borno State, also requires the support of non-medical teams to set up hospitals, hire staff and ensure a steady supply of medicines and goods.

Johannesburg resident Paul Holzweber recently spent three months as a logistics manager at a nutrition project in the state capital, Maiduguri. He shares his story:

When I arrived in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State, last December, to work in administration and supply for a Doctors Without Borders (MSF) emergency nutrition project, I knew the primary goal of our work is to provide medical assistance to some of the hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people (IDPs) in need of nutrition support, care, and medication.

As a non-medical manager, I knew I’d oversee a team responsible for processes that support our medical actions, including running an office, constructing and maintaining a warehouse, and organising vehicles to transport goods, staff and patients.

But what I soon realised is that MSF’s non-medical work has “side effects”.

In a city inundated with displaced people, IDP camps and economic scarcity, our daily work has another outcome: through local purchases and staff hires, we contribute in some small way to stimulating the economy among the communities where we work.

Our project employs around 100 national staff members, including doctors, nurses, drivers, and guards, as well as our busy and determined purchaser, Maina.

Maina grew up in Maiduguri, and has lived through this current crisis. At the age of 25, he has already worked in supply for another organisation doing food distributions in the city. Now he handles all the purchases on our project’s behalf, spending most days negotiating prices with vendors in town.

Each morning, Maina and I meet in our make-shift office behind our house to plan the day’s activities. We get the different supply requests assessed and approved. Then he goes out to the marketplaces and local suppliers to collect quotations and so the negotiations begin.

Our activities require a lot of non-medical purchases, including food for our patients and teams, furniture for our projects, stationary for daily administration, and fuel for the vehicles. More specialised items and medication are ordered from the capital Abuja, or internationally, but there is a wide range of goods we prefer to buy directly from the community.

Once the goods are bought, Maina arranges transport to deliver them to various locations where they are needed: soap to the IDP camps, blankets to the clinic, diesel to the borehole pump, printer cartridges to the office, and so on.

The local economy in Maiduguri is under extreme stress, having lost most of its supply lines from the surrounding areas due to the ongoing conflict. Goods that are transported in come from far away. Although there are supermarkets stocked with international imports, the high cost means most are not accessible to a big portion of the population who have become dependent on food distributions by different relief agencies, including MSF.

So our daily purchases add to the financial ecosystem, bringing in more business for local shop owners and, in turn, bringing funds to people in the community. The suppliers get their share, so do the truck owners and drivers who do the transport, and the daily workers we engage to do the loading and unloading of supplies. Similarly, when we need something built, like a new block of latrines in the IDP camp, it’s the local contractors and their employees who gain additional income from the work.

Formal employment – and a stable income – is often scarce in the areas where MSF operates, especially Maiduguri. It is a full, bustling city, but the huge numbers of displaced people means many live in extreme poverty. On some local vacancies we advertise, we receive several hundred applications. By employing people from within the communities where we work, we get a chance to not only hire staff to enable better patient care, but to also contribute economically by giving people work, an income, and a different perspective.

In many cases, our locally hired colleagues say they have learnt more about formal employment, savings plans, contracts, taxes and pension funds working with MSF. Samuel, our water and sanitation technician working in the IDP camps attached to our project, says he plans to save his salary to buy a computer that will provide him even better prospects in future.

Through task-specific training, we enable staff to do their work and have on-the-job-training that increases their efficiency and capabilities. These range from specific medical training to simple support functions and coaching.

Training is where my personal passion lies. In Maiduguri, I worked to empower my small supply and administration team to increase their performance. After noticing gaps in math and computer literacy skills, I started an applied mathematics class on weekends which both Maina and Samuel, and other members of the medical team, attend. They are able to not only refresh their mathematics, but also learn the use of Microsoft Excel spreadsheet calculations which they can now apply to their daily work. Both Maina and Samuel are keen on learning to calculate the capacity of a de-sludging truck we may hire for our water and sanitation activities, and how to calculate prices per unit to make them comparable.

I am pleased to know that when MSF finally leaves Maiduguri, we will leave a positive economic impact – even in a small way. Over 100 people, who have learned a lot during their engagement with us, now have a better chance of improving themselves and contributing to the development of their own communities in future. And what better “side effect” to have, on top of the lives we get to save.

Find out more about MSF’s activities in Nigeria.