Angela Jambo welcomed us warmly into her modest home in Chitungwiza, one of Zimbabwe’s largest and fastest-growing dormitory towns, located 25 kilometres southeast of the capital, Harare. Her beaming smile masked a long, painful journey. Without hesitation, Angela took us back to the year 2000, the year she was diagnosed with HIV.

Back then, it was a death sentence,” she said.

Zimbabwe was not offering antiretroviral treatment (ARVs), and people living with HIV relied on "positive living" methods (Back then, positive living meant embracing a proactive lifestyle focused on traditional nutrition, herbal remedies, mental well-being, and peer support to manage life with HIV.) and home-based care for the bedridden. The situation was dire, but Angela and a few other women came together and marched to State House, the President’s official residence, to share with him their grievances. They did not manage to get to the State House due to security reasons, but eventually they secured a meeting with the then Vice President of Zimbabwe.

That meeting became one of the many milestones that led to the introduction of ARVs in Zimbabwe five years later.

Since then, Angela has spent her time advocating for others living with HIV. With strong donor support, especially from the U.S. Agency for International Development USAID, access to treatment expanded, support groups grew, awareness increased, and hope renewed.

Media reports show that from January to June 2025, Zimbabwe recorded 5,932 AIDS-related deaths, up from 5,712 during the same period in 2024. While the cause of the increase remains unclear, the trend raises concern.MSF

But that hope is now crumbling since U.S. President Donald Trump issued a sweeping executive order that froze most foreign aid, followed by an aggressive rescission proposal aimed at cutting billions in global health and development funding. Over 170 days later, today, the USAID has effectively ceased operations, the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) faces an uncertain future, and the administration announced the end of U.S. funding for UNAIDS, the United Nations’ flagship programme for HIV/AIDS. More donor countries, including the Netherlands and the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), have announced reductions in their financial support in Africa, a situation that will further cripple Zimbabwe’s already overstretched health sector.

Angela felt the blow firsthand. She received the message to stop all activities via a WhatsApp group for volunteers under USAID projects. Immediately, nutritional aid, food hampers, psychological support, and educational materials disappeared. Parents and guardians of children living with HIV were thrown into confusion. Some schools began turning children away. Those preparing for final exams were unable to register, as USAID had been their sole source of funding for school fees, including examination registration fees. Her community was left reeling.

Angela’s voice cracked as she recalled an 11-year-old boy born HIV-positive who lived nearby. After learning the truth about his medication, he became violent and blamed his mother for his status. Angela counselled him and introduced him to a support group, which changed his life.

That boy, and many like him, weigh heavily on Angela’s heart.

“Support groups were everything,” Angela said.

“Now I see these children walking aimlessly as we are no longer conducting any support group activities. It’s stressful and disturbing. These children had found a family in our groups. Now, all of that is gone,” she adds.

Now, we are seeing condom stockouts, something we have not been experiencing lately. Preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention is no longer given to new clients. We seem to be going backwards.Beloved Mhizha (not his real name), a sex worker and a former micro-planner with The Centre for Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS Research Zimbabwe (CeSHHAR Zimbabwe)

Angela’s story is far from unique.

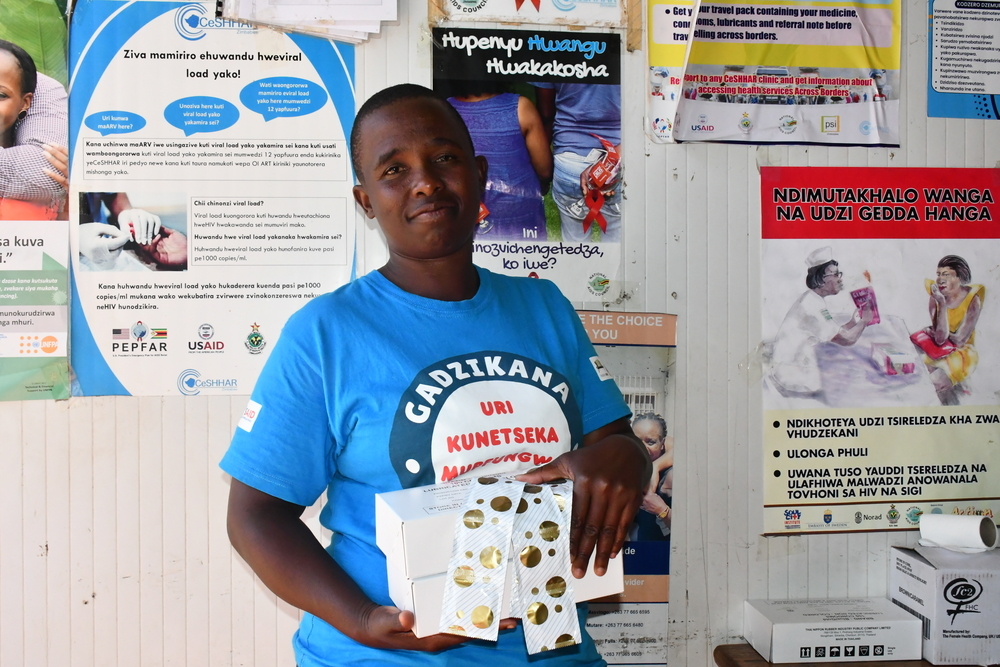

In Mbare, Beloved Mhizha (not his real name), a sex worker and a former micro-planner with The Centre for Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS Research Zimbabwe (CeSHHAR Zimbabwe), an organisation that specialises in population health research and HIV/AIDS programming, has watched, helplessly, the network of sex workers he worked with collapse.

“Before the funding cuts, clinics were well-stocked with medication and supplies,” he said.

“Now, we are seeing condom stockouts, something we have not been experiencing lately. Preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention is no longer given to new clients. We seem to be going backwards,” he adds, shaking his head in disbelief.

He described how services that they accessed with ease have either become inaccessible or prohibitively expensive.

“We used to get medication for free. Now, we must travel long distances or go to private clinics where we pay for the medication for some drugs. Even the gas used during cryotherapy, a common treatment for genital warts that uses extremely cold temperatures to freeze and destroy the wart tissue, is no longer available. Loops (Intra uterine device IUD which act as a contraception) and condoms are in short supply and clinics no longer treat minor ailments like they used to.”

It was tough work, but rewarding,” she said.

“Now, I cannot help anyone, even though I know how to,” she adds.

She used to follow up with clients, especially key populations (In the context of HIV, these are groups that are at higher risk of HIV infection and face social and legal challenges that increase their vulnerability), ensuring they stayed on medication and received proper care. Today, without support from clinics or funding, she is not useful to them.

“It hurts to see people suffering while I stand by with my hands tied,” she said.

In Glen View, Harare, Natasha Ngwenyeni, a community volunteer with the Zimbabwe Association of Church-Related Hospitals (ZACH), has also witnessed a painful decline. Her work involved supporting key populations to access healthcare services and pushing for inclusive policies.

“The work we did brought dignity to people who had long been ignored by service providers,” she said.

“But with USAID said to be closing for good in September this year, I fear the worst is yet to come. Already, key populations are beginning to shy away from being served at local clinics as they fear being judged by service providers.”

Doctors Without Borders (MSF) Country Representative Zahra Zeggani-Bec highlighted that the funding cuts are already having far-reaching consequences.

“We are seeing a total collapse in community-based and prevention programming, especially for key populations who are now entirely left behind,” she said.

“The cuts are not just hitting programme activities and medical stocks; they are crippling the logistical backbone of HIV care. Transport for distributing supplies has all but vanished. Confusion reigns, with services changing daily or weekly, leaving patients unsure where to go and breaking continuity of care. We are also deeply concerned about looming stockouts of essential drugs, HIV test kits, and lab equipment, particularly the cartridges needed for the GeneXpert machines that are central to HIV and TB diagnosis,” she adds.

The consequences of ongoing and newly announced funding cuts threaten to reverse decades of hard-earned progress in Zimbabwe, where an estimated 1.3 million people are living with HIV significant achievements, including reaching the UNAIDS 95-95-95 fast-track targets among the adult population, meaning 95% of people living with HIV know their status, 95% of those diagnosed are on treatment, and 95% of those on treatment have achieved viral suppression, warning signs are emerging. Media reports show that from January to June 2025, Zimbabwe recorded 5,932 AIDS-related deaths, up from 5,712 during the same period in 2024. While the cause of the increase remains unclear, the trend raises concern.