While close to 630,000 people remain displaced by the ongoing conflict in Cabo Delgado, northern Mozambique, over 540,000 people previously displaced have returned to their areas of origin1. The coastal town of Mocímboa da Praia and other parts of this district, which were heavily impacted by the violence, now host to many of these returnees. Luis Angel Argote, coordinator of Doctors Without Borders (MSF) in Mocímboa, explains the challenges of rebuilding life from zero with the ghosts from the past.

What situation did the returnees find in Mocímboa?

The first attacks in Cabo Delgado took place in Mocímboa da Praia in 2017, followed by more severe violence. In 2020, the town was taken over by members of a non-state armed group, but in August 2021, Mozambican and Rwandese armed forces retook control. Since then, around 176,000 people who had fled from the district have returned following the improvement in the security situation, according to United Nations figures.

Mocímboa today has the largest number of returnees in Cabo Delgado and is the area of return with the highest needs, followed by the neighbouring district of Palma. Palma hosts the Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) megaproject, the biggest private investment in Africa, and was at the centre of attacks in 2021 that attracted international media attention.

Having arrived in Mocímboa after years of being displaced, families were confronted with total destruction. Most public buildings, including schools, hospitals, health centres and water infrastructure, were destroyed, as well as shops, markets, stores, and banks. Almost every building was hit at least by one gunshot or burned to some extent. Most families have had to face the harsh reality of needing to rely mainly on humanitarian assistance. People have no jobs or outlook on the future.

What are the main needs of families returning to Mocímboa?

The harsh conditions of displaced people are typically in the spotlight in Cabo Delgado, but often, life for returnees is equally difficult, and their needs can be quite similar. The returnees are mainly requesting support with food, water, shelter, healthcare, including mental healthcare, and education. MSF is still one of the very few organisations or bodies providing humanitarian assistance here, and it is essential to mobilise additional assistance.

Most health infrastructure was destroyed and needs to be reconstructed to ensure access to healthcare. There is an urgent need for additional health professionals, medicines, and medical equipment to make health centres and the hospital functional again. Patients are waiting for long hours and sometimes have to share beds due to the insufficient number of health professionals and facilities available. Only one out of seven health centres operational before the conflict is now functioning, and rehabilitation of the main hospital and maternity service in the district is still pending. Ambulance drivers do not yet feel comfortable responding to emergencies during the night due to concerns about the security situation.

The conflict has had a significant impact on people’s mental health. Returning meant re-living the traumas experienced. The attacks were brutal and left no one untouched. Many had or saw their parents, siblings, grandparents, children, friends, and neighbours assassinated, decapitated, or killed by gunfire. Some lost their entire family. More than 50 per cent of the patients we have seen in our mental health sessions had separation or loss as a precipitating event, and 19 per cent are direct victims of violence. We have seen cases of elderly people either taking care of their grandchildren or having lost their whole family during conflict. We have seen orphaned minors having to take care of other minors.

For most families, every day is a struggle to get something to eat, despite the efforts of some humanitarian organisations and the solidarity within the community. Some people cultivate whatever they can close to their houses as they don’t dare to tend crops in the forest anymore due to security concerns. Food is rationed within each family. If it weren’t for the fertility of the soil in Mocímboa and the access to sea and rivers for fishing, many people would experience starvation. Some have managed however to build nets to fish, buy seeds and machetes for agriculture, and slowly started rebuilding their lives.

The water network of Mocímboa was also destroyed. Of 102 public water fonts and boreholes assessed by MSF in Mocímboa town, only 23 are working – five recently built by MSF. This means that for a population of more than 53,500 people in Mocímboa town, the ratio is one water point per approximately 2,300 persons. To access safe water, families must walk miles and wait in lines for hours to fill as many buckets as they can manage. The lack of water and latrines also prompts concern about water-borne diseases such as cholera.

As most schools were destroyed during the conflict, children can often be seen having classes under mango trees – but for just two hours per day, as the same teacher gives classes to multiple groups.

What is MSF doing in response to the situation?

MSF had previously run a project in Mocímboa, but the team was forced to evacuate in March 2020 as the area was being attacked by non-state armed groups. Through mobile clinics from mid-2021, we progressively reached some areas of the district, and in September 2022, as people started to return in large groups, MSF resumed its permanent presence in the town.

Currently, MSF provides primary healthcare services at the transitory health centre in Mocímboa and through mobile clinics in eight villages within the district. These services include testing and treatment for HIV and TB, sexual and reproductive healthcare, pre and post-natal consultations, and a nutritional and mental health program.

Between January and June, MSF reached over 100,000 people with health promotion activities, conducted 21,600 medical consultations, provided psychological support through group and individual sessions to 14,000 people, treated 7,300 cases of malaria and 4,800 cases of respiratory infections, referred 2,000 patients in need of further medical care, conducted 1,500 sexual and reproductive health consultations, and assisted 600 childbirths. In the first half of 2023, the main conditions seen in our mobile clinics were malaria (33.9%), respiratory infections (22.4%), and skin diseases (16.2%).

MSF has also been helping to rehabilitate health infrastructure, which has included the rehabilitation of the Centro Escola de Formação, close to the main hospital in Mocímboa, which is serving as a temporary hospital. MSF also provided support with the rehabilitation of Quelimane Health Centre, which is supposed to cover the needs of around 16,000 people in the area. To improve access to safe drinking water, MSF distributed soap and chorine solution kits to 16,000 families and is supporting the rehabilitation of water pumps.

What else can you tell us about Mocímboa?

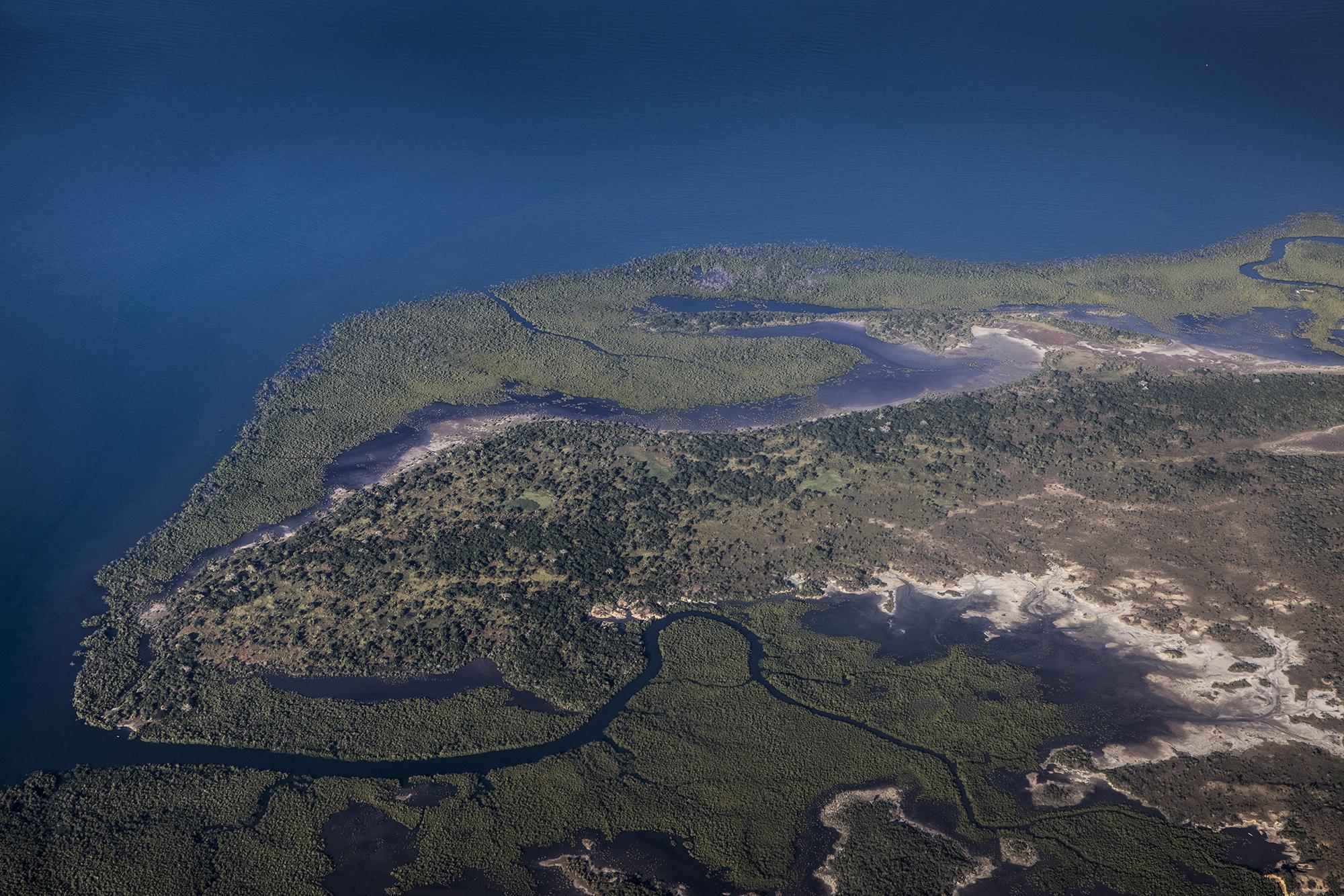

Mocímboa is a special place for its beautiful nature and the strength of its population. There are plenty of coco and mango trees, beautiful beaches, rivers and lagoons, and a deep forest surrounding everything. When travelling by air, you see the magnificence of the Indian Ocean contrasting with the green forest and white sands, as well as the mountains in Mueda and Palma filled with wildlife. Before the conflict, people used to come here on holidays.

In Mocímboa, the community has managed to do what in other places would have taken years: with courage, they have re-started from zero small farms, shops, and civil services the best way they could, with very scarce resources and support. However, substantial needs remain, and we are calling for greater support to address what the community cannot do alone.

MSF has been working in Cabo Delgado since 2019, ensuring access to healthcare for people displaced by the conflict or returning to their homes through community-based services and mobile clinics and through providing support to health centres and local hospitals. In 2023, MSF teams have been present in the hard to reach areas of districts of Macomia, Meluco, Mocímboa da Praia, Mueda, Muidumbe, Nangade, Namuno and Palma. Their activities have included mental health services, primary and secondary healthcare consultations, health promotion, water and sanitation improvements, and distribution of essential relief items.