With the right medications and enough to eat, people with HIV can live long, healthy lives. But what happens when you live in a place where access to these basics is a challenge? Dr Ebenezer Ngwakwe writes..

"She walked into my clinic quietly, with her five-month-old baby wrapped up in her arms. I could easily see the overwhelming emotions she was trying so hard to conceal, as tears started streaming down her face. This was one of numerous similar encounters that would characterize my 11-month assignment with Doctors Without Borders (MSF) in Old Fangak, South Sudan.

Beautiful Old Fangak

As an English speaker, it was just a matter of time before I was offered an assignment in South Sudan, a country in the horn of Africa where English is the official language. Old Fangak is a region in the north of the country, transected by the river Phow. There are no telecommunication networks, no tarred roads and no cars, only boats.

Every evening, as we ride the boat back to our compound, the breath-taking sunset, the chirping birds, the lush green bushes by the riverside, the sound of water splashing on the boat and children swimming by the river bank, temporarily relieves you of all the memories of the suffering sick people in the hospital.

So I pledged, with my right hand on my chest, that my stay here would only bring more hope to these people.

This swampy community consists of about 30,000 people. All of those who I've met have been very friendly, strong and resilient. Despite all the intermittent inter-clan clashes, revenge killings, hunger gap, floods and zero modern infrastructure they keep finding ways to happily move on, hardly ever giving up hope. So I pledged, with my right hand on my chest, that my stay here would only bring more hope to these people.

Hand of hope

So here I was, working in my clinic when that lady walked in. Nya-Cece (real name withheld) is in her early 20s, had her first child at 14, already had two failed marriages and now has a new baby with a soldier husband who lives far away in another community and hardly ever visits.

Listening to her, I knew this was the exact reason I joined MSF, to help people like her.

The tears rolled down her face as she spoke. “I feel all alone, I have no one. My father does not care about me because I had my first child outside marriage. He says I brought shame to his family. My mother remarried and left with her new husband. Now, here I am, HIV positive, with no money, no job and almost no food for my boys”.

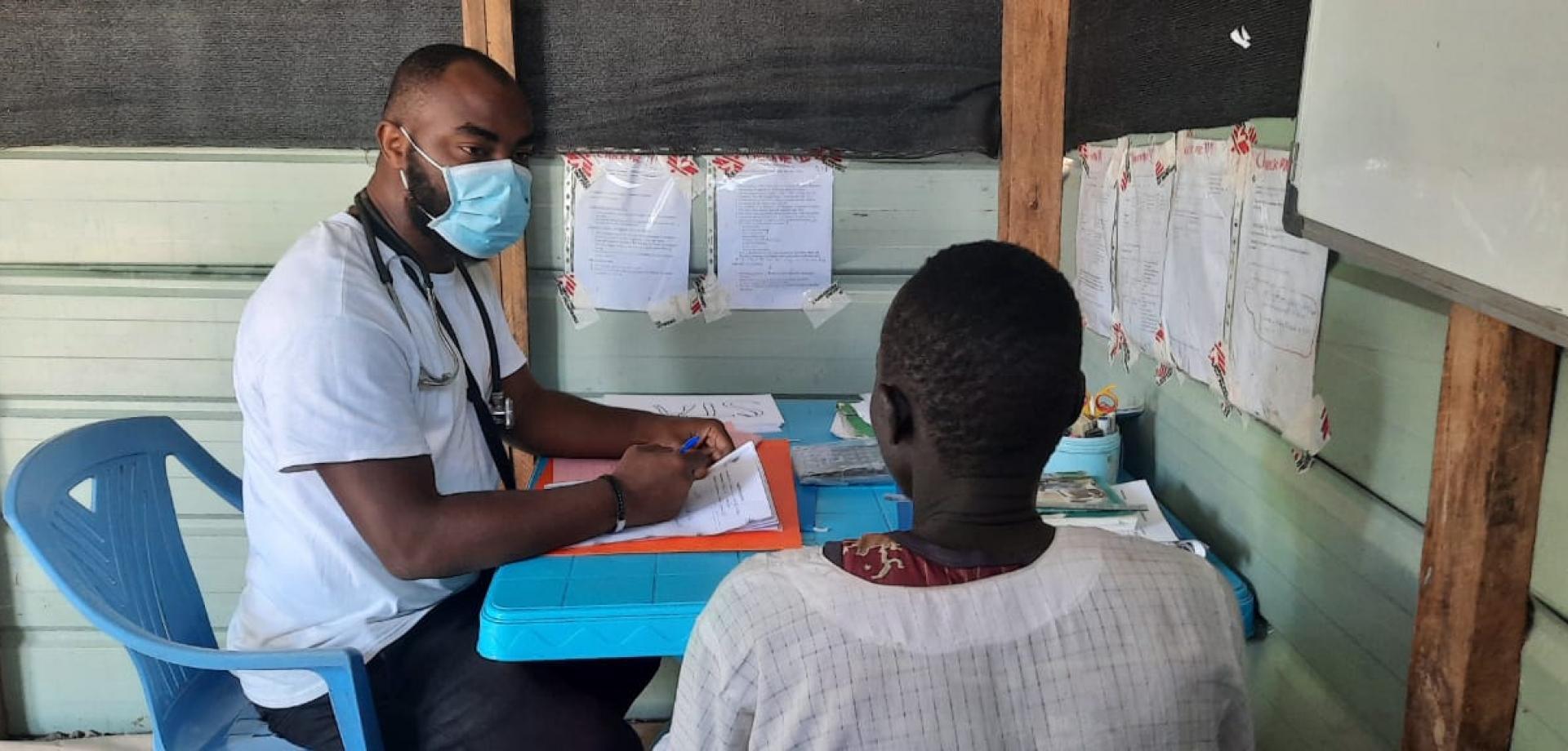

Listening to her, I knew this was the exact reason I joined MSF, to help people like her. According to latest UNAIDS reports, about 190,000 people are living with HIV in South Sudan. Being the major health care organisation in Old Fangak, our MSF teams provides a comprehensive HIV care package via a six-days-per-week HIV clinic that provides counselling and testing services, consultations, in-patient management of opportunistic infections, viral load assays, prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) and community HIV awareness campaigns.

With the help of the MSF HIV counsellor I was working with, we offered Nya-Cece medical care, psychosocial support and linked her to another organisation that provides food. Through this kind of work, we now have 120 patients enrolled in HIV treatment in Old Fangak, up from zero three years ago.

Still, the HIV situation in Old Fangak is very challenging. People have poor access to health care (sometimes, patients walk 72 hours from their village to get to our center), and being known to have HIV is very highly stigmatised in the community.

As well as the weak healthcare system, managing the condition is more challenging for lots of reasons. The "hunger gap" season, when the food from one harvest is finished, and the food from the next not yet ready, hits people hard here, making it more difficult to get enough to eat – vital to maintaining a strong immune system and managing HIV. On top of this, people are frequently forced to move to escape insecurity and widespread flooding, which not only makes it hard to access health care, but also makes it hard for people to make enough money or grow enough food.

Women in Old Fangak

Perhaps the most heart-wrenching thing I have noticed during my time in Old Fangak is the glaring gender inequality in a traditional culture. Like Nya-Cece, most young ladies are already married and have at least one child by the time they turned 18. They mostly don’t have any formal education, therefore they have no jobs and it’s hard for them to earn money.

For instance, I could count only five female medical staff compared to 45 male staff in our hospital. Many women would require a man’s consent (usually their husband's or father's) to access basic care like family planning services or referral to a secondary health center. If he declined, she would be denied the care. It is mind-boggling that in 2020, this is the reality of women in Old Fangak. Surely a lot needs to be done to address this gender inequality.

The New Fangak experience

Despite the friendly nature of the people in Old Fangak, the incessant inter-clan armed clashes made the security situation very precarious and affected access to medical services negatively.

In May, our team was evacuated to New Fangak. The events leading to this evacuation started two days earlier when the government unsuccessfully tried to disarm a local armed youth group. That morning, there was exchange of gunfire between the two parties disrupting hospital activities as we were quickly whisked away from the hospital back to the international staff compound.

The next day, we could see women and children fleeing Old Fangak in droves, in anticipation of war. On that morning of evacuation, we discharged stable patients, and suspended all activities. The unstable patients needed continued care, so they came with us to New Fangak. Some of the South Sudanese staff evacuated with us to help care for them, while others fled Old Fangak to seek safety elsewhere.

When we first reopened, it was extra busy and the team had to work extra hard to see all the patients.

In New Fangak, news of our arrival spread so fast, that in no time, people started coming for medical care. We even resuscitated some war-wounded people and referred them on to other medical facilities for surgical care.

But I could not stop thinking about all the patients in Old Fangak who would now be denied access to health care for one week. What about the patients with type 1 diabetes who depend on us for their daily Insulin? What about the people living with HIV who would need their drugs? What about the women in labor who would need obstetric care? The list goes on and on.

Life in New Fangak was very challenging. The unfriendly hot weather, the lack of drinking water, the lack of Wi-Fi to communicate with my family and friends, the mosquito bites and snakes all made New Fangak a very challenging experience for me.

Eventually, at the end of seven days, our team, who by now had become a band of seven brothers, gratefully returned to Old Fangak to resume hospital activities.

When we first reopened, it was extra busy and the team had to work extra hard to see all the patients. In the HIV program, we had to implement multi-month drug prescriptions to make sure patients have extra supplies of their medications in case of future emergencies.

Looking back

I near the end of this assignment with a deep appreciation for MSF's relevance in Old Fangak. Nya-Cece is just one example. I saw her again a week ago and she was doing much better, taking her medications regularly and taking care of her boys.

Looking back, it has been an impactful 11 months of offering care and hope relentlessly.