A state of silent crisis

Some 38 million people in the world are living with HIV/AIDS, over two-thirds of them in sub-Saharan Africa. While Central African Republic (CAR) is considered a low HIV prevalence country compared to many southern African countries, it is in a particularly critical situation, fuelled by extreme poverty, pervasive violence, a dire shortage of health facilities and health staff, long-existing supply chain issues for lifesaving antiretroviral (ARV) medication, and significant barriers to early detection and care for the people of CAR.

As a result, HIV remains a leading cause of death in the country. Last year, around 4,800 people died of HIV/AIDS in CAR, while some 5,500 new cases are confirmed every year.

A deadly cocktail of obstacles

“While CAR has the highest HIV prevalence across the West and Central Africa region, fewer than half of the estimated 110,000 people living with HIV are on ARV treatment,” says Laurent Lwindi Mukota, HIV medical advisor for Doctors Without Borders (MSF). “The situation is even more alarming for children: of under-15s who are aware of their HIV status, fewer than a quarter are on treatment.”

Ranked as the country with the lowest life expectancy in the world and plagued by years of conflict and insecurity, CAR is utterly dependent on insufficient external funding for its response to HIV. Few of the limited number of health facilities in the country offer HIV testing and care, and many people living with HIV have to make long and often dangerous journeys to find a clinic where HIV services are available. Those who do manage to reach a clinic sometimes find empty shelves instead of the much-needed drugs, making it impossible for them to continue their ARV treatment.

“In a country where most people live on less than R 30 (US$2) a day, financial barriers to care are exacerbating this situation,” says Marie Charlotte Bantah Sana, head of the programme against communicable diseases, Ministry of Health and Population. “Most people need to pay to get an HIV test, and then have to pay for several extra tests before being allowed to start treatment. As a result, 30 per cent of all patients invited for a pre-treatment assessment do not come back to start their medication.”

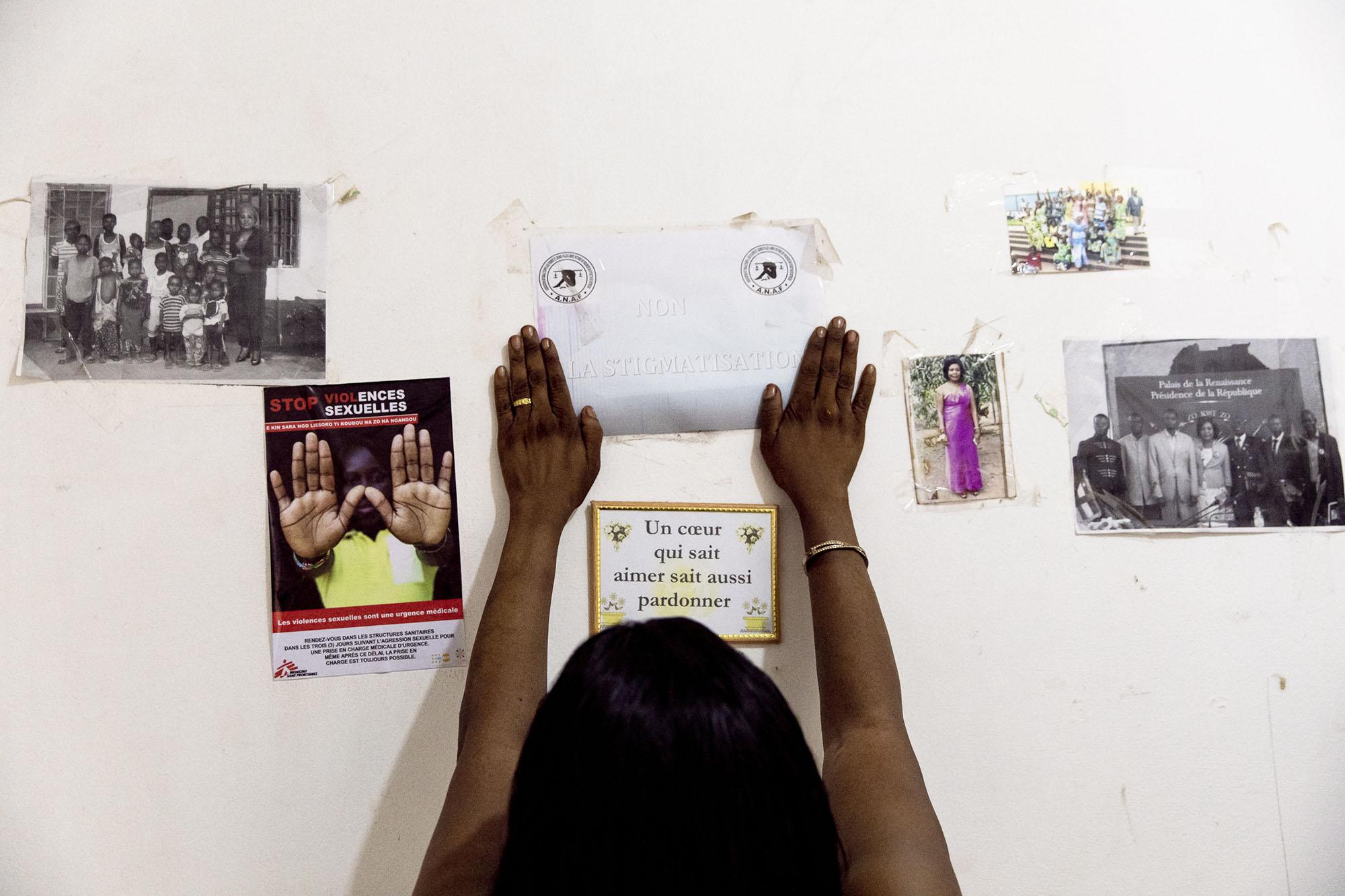

This deadly cocktail of obstacles, combined with the end of free testing due to lack of funds, as well as with poor information and stigma about the disease, help explain why close to two-thirds of HIV patients in CAR are diagnosed with advanced HIV by the time they start ARV treatment.

Supporting patients with advanced HIV

In this critical environment, MSF works closely with the Ministry of Health and Population and engages with other key players to support access to diagnosis, treatment and care.

In Bangui, the capital of CAR, HIV prevalence is twice the national average. Since late 2019, MSF teams provide free medical care and psychological support for patients in an advanced stage of the disease who are also co-infected with tuberculosis (TB) – the only organisation in Bangui to do so. They also implement a referral system between the hospital and peripheral health centres, which will be further developed over the coming months.

One year after the start of MSF’s HIV/AIDS project at Bangui’s Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Communautaire, 1,851 patients had been admitted for HIV treatment, including 558 patients newly diagnosed with HIV.

“I was at the hospital accompanying a relative when I started having a fever and symptoms of malaria,” says Reine, a 34-year-old widow and mother of two. “During the consultation, the medical team offered to get me tested. This is how I stumbled onto my condition. I was immediately put on treatment. I had to go back to the hospital a few days ago because I got very sick again. I am now cared for and I feel better day by day.”

Treating HIV/AIDS in the Central African Republic

Anita, a mother of six, also had no idea she was HIV-positive, despite feeling unwell for some time. “It has been a while that I’ve felt unhealthy, but I did not know I had AIDS. I fell sick two weeks ago and was brought to the hospital to receive care. I learnt about the disease when I arrived here.”

Outside Bangui, MSF is providing treatment for patients with advanced HIV in Paoua, Carnot, Kabo and Batangafo.

Increase access to treatment through community groups

To help increase people’s access to treatment, MSF has set up ‘community ARV groups’ in Bambari, Batangafo, Bossangoa, Boguila, Carnot, Kabo, Paoua and Zemio. In this system, groups of patients who are living with HIV and in a stable condition designate one of their members to go and collect the drug refills for the coming months for the whole group, reducing transport costs and time spent in medical consultations.

As well as making treatment more accessible, these groups also help patients self-manage and participate in their treatment and encourage peer support and adherence to treatment, in a country where stigma against people living with HIV remains a harsh reality.

Members of these groups are key advocates of HIV prevention and have proved that a community approach can be extremely effective. They help ensure that patients can continue their treatment even in difficult or dangerous circumstances, as in CAR, where flare-ups of violence can make travelling risky.

This community-led initiative proved to be even more important in the context of COVID-19, when access to health structures was reduced, notably due to the infection prevention and control measures necessary to prevent the spread of this virus.

“In our group, one member goes to the hospital every year to get the treatment for the 10 other members,” says Serge, part of an MSF-supported community ARV group in Carnot. “This system is important because some people are ashamed to go to the hospital to get their HIV treatment.”

By the end of 2020, MSF had helped set up 276 community ARV groups in CAR, representing some 2,300 patients.

“In all projects where the community ARV group system has been implemented, the number of people living with HIV who are joining these groups is constantly growing,” says Laurent Lwindi Mukota. A similar system has been set up in other African countries where HIV is a significant issue, including Mozambique, South Africa, Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In 2019, a total of 6,600 people living with HIV were on ARV treatment via MSF-supported health facilities in CAR. Yet, there is still an important work to do in order to decentralise, destigmatise and make sure the HIV test and treatment are free and accessible to all.

While some progress has been made over the past decade, the weakened health system, exacerbated by years of violence, displacement and insecurity, continues to struggle in its fight to lift the barriers to the HIV response in CAR. There is an urgent need to increase efforts – and to increase investment – so as to put free HIV testing and care within reach of everyone in the country.