On 9 July 2021, the Republic of South Sudan marked its tenth birthday. This significant milestone is also marred by the bloody legacy of its first decade, including a five-year civil war.

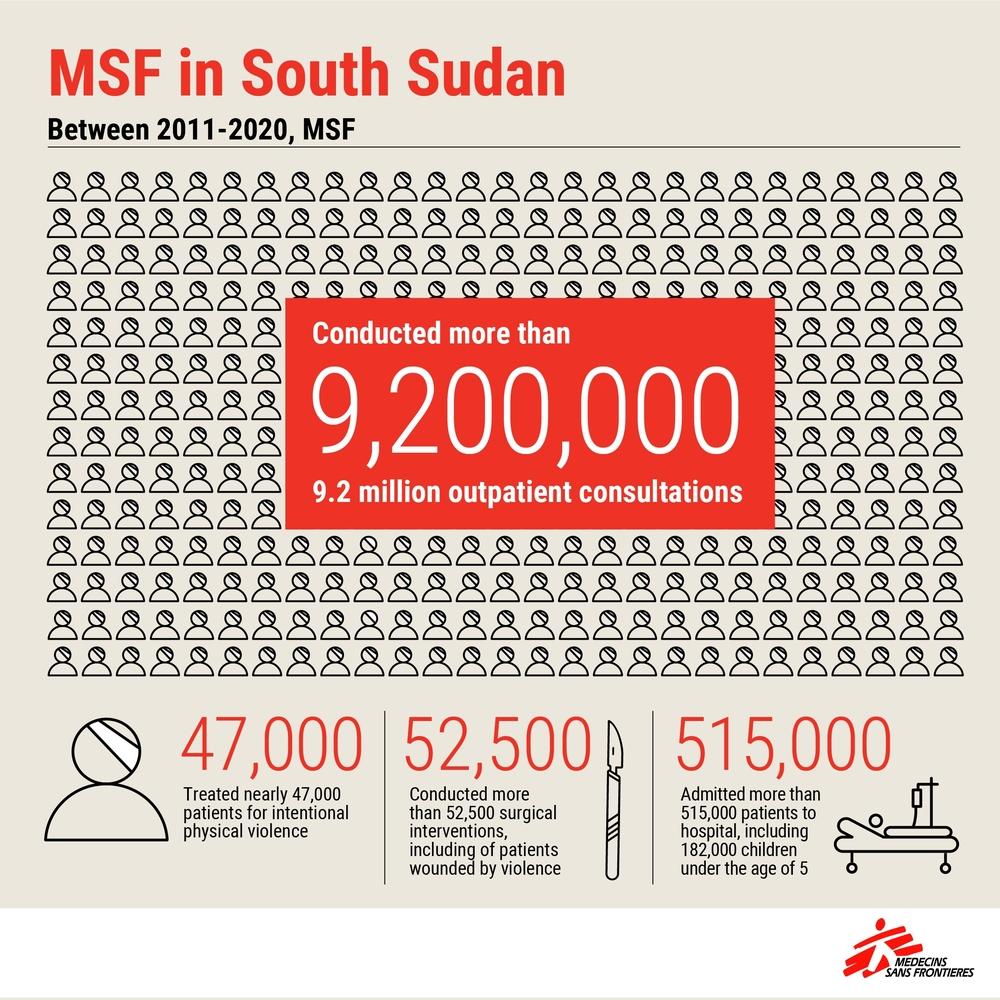

A new Doctors Without Borders (MSF) report, South Sudan at 10: an MSF record of the consequences of violence, offers a consolidated account of MSF’s experience in South Sudan since 9 July 2011. It seeks to serve as a record and reminder of the human toll of violence since independence, as seen by MSF – through its staff and patients.

Independence to civil war

At independence, South Sudan was grappling with at least 30 humanitarian emergencies. Parts of the country were engulfed in increasingly fierce intercommunal clashes, and there was renewed conflict in border areas with Sudan. Despite the challenges, the first years in the post-independence period were a time of anticipation and optimism and, for most of the country, it was a period of relative peace.

However, by December 2013 – less than two years after independence – the country had rapidly imploded into civil war, quickly exposing the fragility of the emerging young state.

"After these 22 years of civil war came, then there came independence in 2011. The whole population was joyous. We were happy because a new country was born... but all this hope and dreams became all of a sudden no more." – MSF staff member, Yambio, August 2019

Extreme violence

The five-year conflict is estimated to have led to nearly 400,000 deaths, many the result of ethnically motivated targeting of civilians, including children and the elderly. Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) has been used as a weapon of conflict, with systematic ethnically and politically motivated attacks.

Some of the most extreme violence was conducted in places of refuge and sanctuary, including state hospitals, where patients and people seeking shelter were killed in a series of brutal attacks. Millions of people have been displaced, often multiple times, inside and outside South Sudan. This includes hundreds of thousands of people who sought shelter in Protection of Civilian (PoC) sites, inside the bases of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS).

Since independence, 24 of MSF’s South Sudanese staff have been killed by violence, five while on duty. All of MSF’s patients, staff and their communities have been impacted directly and indirectly by conflict and violence.

Deaths from preventable diseases

Across the country, people have been subject to destruction, displacement, disease, and death. Violence disrupts access to healthcare, including routine vaccination, while increasing the risk of disease transmission and food insecurity.

There have been repeated failures to ensure dignified living conditions for people in refugee camps and PoC/Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) sites. Instead, people fleeing conflict and violence have, over and again, been forced to live in deplorable conditions – with basic requirements for living space, water and sanitation unmet, far below the minimum emergency thresholds for survival.

At its worst, MSF has recorded three to five children a day dying from preventable diseases – such as malaria – in different refugee camps and PoC sites. Meanwhile, people forced to live in the open, in the bush and swamps, have repeatedly been exposed to disease and extreme hunger.

In some areas, conflict brought a resurgence of kala azar, the world’s second-largest parasitic disease. In addition, there have been measles, hepatitis C and cholera outbreaks, amongst others.

Mental health

Millions of people in South Sudan have been repeatedly exposed to traumatic events. MSF has witnessed increases in suicide attempts and has worked with patients coping with post-traumatic stress disorder.

"The most difficult thing to be South Sudanese is the fear. People facing in fear. People sleeping in fear. So, this creates a lot of trauma on people because people are not free like when we first got our independence." – MSF staff, Mundri, August 2019

The impact of protracted conflict and repeated humanitarian crises in South Sudan is worsened by a weak, chronically underfunded, healthcare system, destroyed in many areas and largely neglected in others. In 2020, of approximately 2,300 health facilities, more than 1,300 were non-functional. Less than half (44 per cent) of the total population and just 32 per cent of internally displaced persons live within five kilometres of a functional health facility.

Continuing humanitarian crises

Despite a peace agreement in 2018 which ended five years of civil war, and the formation of a unified government in early 2020, the situation remains volatile in many areas. In 2019, South Sudan saw a resurgence of subnational conflicts and factional fighting, which has since escalated in 2020 and 2021.

Today, 8.3 million people – more than two-thirds of the population – are estimated to be in dire need of humanitarian assistance and protection. Today, in what is the largest refugee crisis in Africa, 2.2 million South Sudanese people are sheltering in neighbouring countries. More than 1.6 million people remain internally displaced. Even in a best-case scenario, South Sudan will remain vulnerable to humanitarian crises for the foreseeable future and will need assistance for some time.

South Sudan’s leaders must make every effort to ensure civilians' safety and security and an environment conducive to the delivery of humanitarian assistance, independent of any political agenda.

“My hope for the future for the next 10 years is a transformed society, a transformed community where we can live and co-exist among ourselves. "MSF staff member, 22 April 2021

“My hope for the future for the next 10 years is a transformed society, a transformed community where we can live and co-exist among ourselves. Where I see someone is my brother. I see someone is my sister … Where I can just move without any restriction. Where I can express my feelings, to anyone, regardless of their race, regardless of their tribe. And this is the society that I'm longing for in the next 10 years … It’s the young generation that will inspire the generation that is coming after us,” MSF staff member, 22 April 2021.

For nearly 40 years, the area that constitutes South Sudan has been amongst MSF’s highest global priority countries, in terms of operations, employment and financing. As the young nation moves into its next decade, MSF remains committed to the people of South Sudan.