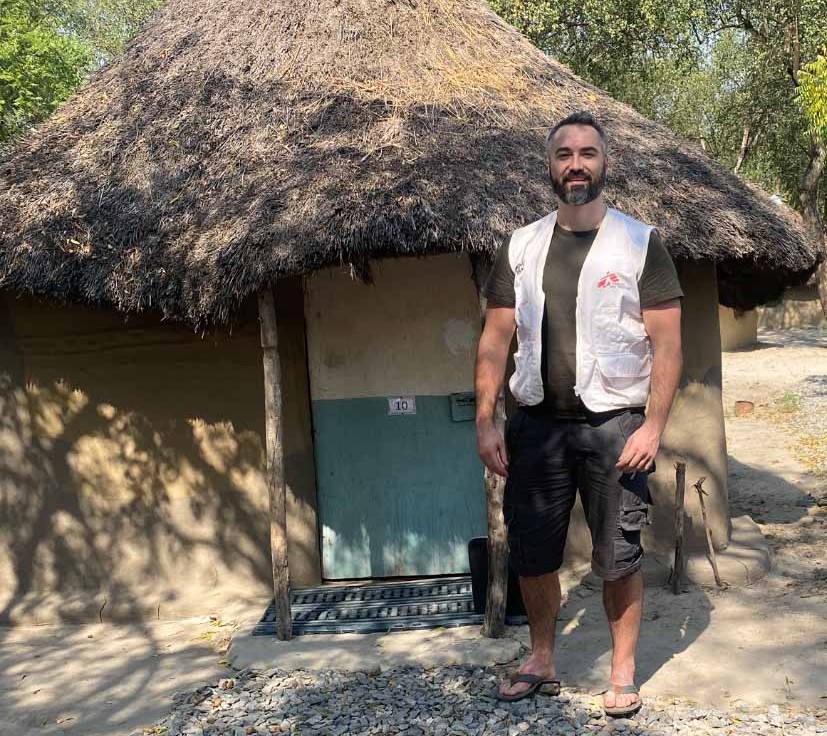

On International Snakebite Awareness Day (September 19th), we hear from Dr Mark McNicol, who recently returned from Doctors Without Borders (MSF) assignment in Lankien, a remote rural area in Jonglei State, South Sudan, where being bitten by a snake can mean profound and long-term impacts for people.

If you get bitten by a snake in rural South Sudan, there are a few things that will happen to you.

One: you could die. Children are particularly vulnerable. Accessing health care in rural South Sudan means walking, and depending on where you live, it might be over a day’s walk to the nearest health centre. Many people die from a snakebite before they can reach help.

Two: you might live close enough to a healthcare facility to walk or to have family members carry you to get treatment like antivenom, wound care, painkillers and antibiotics. If the healthcare facility you arrive at doesn’t have antivenom or it has expired, you may still lose your life.

Three: you could survive without treatment. You’ll experience potentially significant pain, swelling and other symptoms. You may be left with a chronic wound from the bite itself, or it may heal over. Maybe it will scar you, but you’ll continue with your life.

The MSF hospital is in the small town of Lankien in Jonglei State, and is one of the only healthcare facilities in the area. You would expect to see fewer snakes in built-up areas, but we regularly received patients with snakebites.

However, during my assignment, I didn’t see a single case where someone was rushed into the ER immediately after a bite. What we did see was people who came to the hospital months after they’d been bitten, often when the hidden consequences of the bite were finally coming to the surface.

One woman who came into the hospital had been bitten on the ankle, four or five years before. The first thing noticeable was the strong smell of infection — it was powerful, even just walking into the same room. I knew before seeing her ankle that it would be bad.

Even while the surface wounds may be healing over, the bacteria can be multiplying, causing infection and eroding the bone. This is also something you see in conflict zones, in patients who have gunshot or shrapnel wounds without access to proper treatment.

Over time, the deep infection can spread to such an extent that it breaks through the surface of the skin again, causing an open wound. To be clear, this doesn’t happen in every case of untreated snakebite. But patients like this do come to Lankien, and the woman with the infected ankle had one of the worst cases I saw.

The treatment for bone infection is antibiotics, but when it’s particularly severe, patients will need surgical debridement (where the infected tissue is removed) or even amputation. Our hospital doesn’t have an operating theatre, so we use telemedicine to consult with surgical colleagues in other MSF projects. Patients who need surgery have to be transferred by plane.

It was clear that antibiotics were not going to be enough for the lady with the infected ankle. This raised the question of amputation.

This was a complicated decision, as it meant she would have to rely on crutches in an area where almost all travel is done by foot, sometimes over long distances, and often over difficult terrain. But without the amputation, the infection would spread and get worse. She had been through years of pain, and the strong odour from the infected tissue meant that she was also facing stigma in the community.

In the end, the woman and the team agreed that amputation was the best option. My colleagues arranged for her to be flown on our small supply plane to another MSF hospital, where they had the facilities and staff to do the operation safely.

Around the world, MSF works with governments, treatment providers, donors and communities to try to bring about change for people affected by snakebite.MSF Doctor Mark McNicol

Snakebites are a neglected health crisis, and an ambitious approach is required to tackle it. While part of this is about access to affordable, good-quality antivenom, this may still be challenging for the most remote communities, which is why we’re also calling for increased investment in community awareness, first aid and preventing bites in the first place.

The woman’s operation went smoothly, but the impact of being bitten is going to be with her for the rest of her life. Urgent change is needed to ensure that fewer people have to face the life- and livelihood-threatening consequences of this very neglected ‘disease.’