Year in Review 2023: Conflict was a major driver of human suffering and vulnerability in the year 2023, causing many thousands of deaths worldwide and displacing record numbers of people. As in previous years, assisting communities affected by violence was a significant component of Doctors Without Borders (MSF) programmes. We also responded to disasters and disease outbreaks and worked to improve healthcare for refugees, migrants, and other marginalised people.

The terrible consequences of war on people’s lives

In mid-April, when war suddenly broke out in Sudan between the Sudanese army and the paramilitary group, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), our teams quickly adapted their activities to respond. Fighting was intense in the capital, Khartoum, and across large swathes of the country.

As a result, 8.5 million people have been displaced, most of them within Sudan. But over 1.8 million have fled to neighbouring countries, including Chad, South Sudan and Ethiopia. The war in Sudan has garnered very little of the world’s attention, and support from other organisations is sometimes non-existent; in some areas, MSF is the only international humanitarian organisation present.

Assisting people injured and displaced by the war proved extremely challenging. Local authorities blocked the delivery of critical medical supplies to areas under RSF control, forcing us to temporarily suspend activities in some facilities, including surgery at Khartoum’s Bashair Hospital. Visas for international teams to enter and support exhausted Sudanese staff became hard to obtain. At the end of the year, many people who remained in Sudan were struggling to obtain medical care, food and water, while those who had crossed the borders found themselves living in dire conditions in camps. Our teams in Chad and South Sudan treated thousands of Sudanese refugees for violence-related injuries and rape, and infectious diseases seen in the poor conditions of the camps.

On 7 October, Hamas, the organisation governing the Gaza Strip in Palestine, launched a massacre inside Israel, killing around 1,200 people and taking more than 250 hostages. Israel declared war on Hamas and started bombing Gaza. Since then, Israeli forces have relentlessly shelled and attacked residential areas and civilian infrastructure. Israel also imposed a total blockade, cutting off supplies of water, food and other essential goods. Tens of thousands of people have been killed. Over 1.7 million people in Gaza are estimated to be forcibly displaced and living in unsafe, unhealthy conditions; 1.5 million people are crammed into Rafah, on the border with Egypt.

Many healthcare facilities are no longer functioning, due to damage from shelling and incursions and/or a lack of fuel, which is needed to run generators. Those that remain partially functional are overwhelmed with patients and have few staff and almost no supplies. Healthcare infrastructure and personnel – including our own – have been repeatedly hit by airstrikes or bullets. Since 7 October, five MSF staff have been killed in Gaza; we deeply mourn the loss of Mohammed Al Ahel, Alaa Al Shawa, Dr Mahmoud Abu Nujaila, Dr Ahmad Al Sahar and Reem Abu Lebdeh.

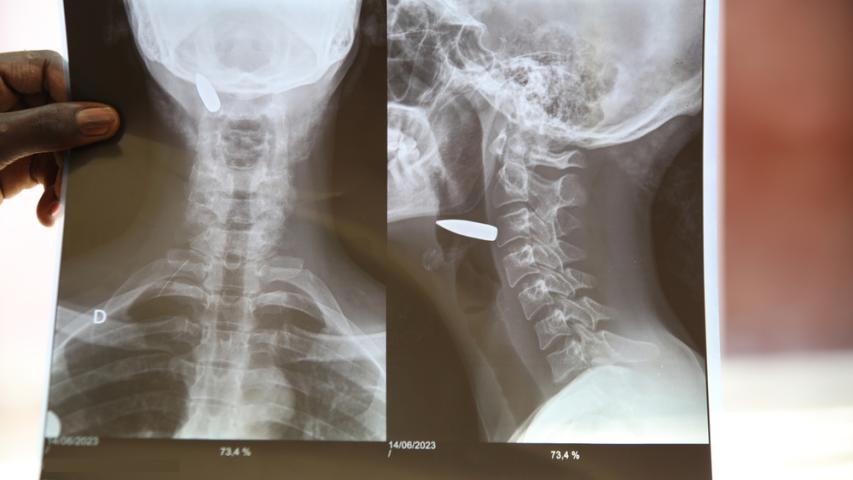

Reorienting our activities to respond has been difficult. Supplies have been hard to get, and the physical space in which we can safely deliver care has diminished. The war has also had an impact on the West Bank, where occupation-related violence has increased; our teams offer mental health support and treat patients for trauma injuries.

At the end of October, conflict escalated in Myanmar, leading to an acute humanitarian crisis. Thousands of people were displaced, and many healthcare facilities ceased to function following attacks and evacuations. Despite insecurity and restrictions on access, our teams assisted displaced people in northern Shan and Rakhine states through mobile clinics and, when forced to suspend direct activities, through community health workers and teleconsultations.

Meanwhile, in Ethiopia, MSF worked to address the immense medical and nutritional needs and support people affected by conflict in the Amhara region. As the war in Ukraine showed no sign of abating, we focused on ambulance services and providing treatment for both physical and mental trauma, including surgery, physiotherapy and mental health consultations.

Providing care amid chronic violence

In an almost-forgotten conflict, civilians continued to bear the brunt of the horrific violence perpetrated by the M23 and other armed groups across the northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo in 2023. Millions of people have been displaced, often multiple times, within North Kivu, South Kivu and Ituri provinces, or forced over the borders into Uganda and Rwanda by the fighting between M23 and the DRC armed forces. Our teams delivered medical care to people living in appalling conditions, including many patients with war wounds and victims of sexual violence.

Explosive violence continued in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince, in 2023, with armed groups fighting each other and the police for control of the city’s neighbourhoods. People were routinely kidnapped and held for ransom or shot on the streets. The high levels of insecurity reduced both people’s access to healthcare and MSF’s ability to provide it – sometimes, it was too dangerous for our staff to travel to work, and on repeated occasions during the year, we had to suspend or close facilities or services. Our facilities in Tabarre and Turgeau stopped activities during the year, following serious incidents where patients in our care were forcibly removed by armed groups – one from an operating theatre and another was pulled from the back of an ambulance and killed in the street.

State forces and armed groups continued to fight across the Sahel region of Africa, destroying communities and livelihoods, and cutting off people from healthcare and basic services. Anti-Western and particularly anti-French government sentiments and changing geopolitical contexts across Burkina Faso, Niger, Mali, and other countries in the region posed many security and logistical challenges for our teams in 2023. These included gaining access to the highest needs and bringing in staff and supplies. The violence sadly did not spare our staff; we mourn the loss of our colleagues Komon Dioma and Souleymane Ouedraogo, who were killed on 8 February when an armed group attacked an MSF vehicle in which they were transporting supplies near Tougan, Burkina Faso.

Responding to disasters

In February, when two powerful earthquakes struck southern Türkiye and northwestern Syria, killing tens of thousands of people, MSF immediately launched an emergency response. We provided medical and mental healthcare, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, shelter, and food in both locations.

We also sent teams to assist people affected by Cyclone Freddy in Malawi and Mozambique in March and Cyclone Mocha in Myanmar in May by offering medical consultations, supplying clean water, and building and repairing latrines.

In September, our teams provided healthcare and medical supplies after floods partially destroyed the town of Derna in Libya. In the same month, we offered mental health support to survivors of an earthquake in southwestern Morocco. Following another earthquake in October, this time in Herat province in western Afghanistan, we helped treat the wounded and donated essential supplies.

Assisting marginalised people

Authorities in Afghanistan and Yemen have increasingly marginalised women and girls from society and severely reduced their access to education and healthcare. We already face a shortage of qualified female healthcare staff in Afghanistan – needed to provide healthcare to female patients – and this is something that we can only expect to worsen with the ban on female secondary and higher education. Both countries require women to travel with a (usually male) relative when they leave the home. In Yemen, paying transport costs for two people to visit a hospital, rather than one, is unaffordable for many families, while in Afghanistan, women often have to wait for someone to be available to accompany them or their child to a health facility.

In 2023, we continued to assist people who had made the dangerous journey through the Darién Gap, the heavily forested region between Colombia and Panama, on their way north to Mexico and the United States. Over half a million people – including many families and children – made the crossing, twice the number in 2022. Our teams treated patients for conditions and injuries caused by their arduous journeys, as well as many victims of violence and sexual assault, in Panama and other countries along the migration route, including Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras.

We treat refugees, migrants and asylum seekers who have been subject to inhumane migration policies. From the Aegean – where we provide care to people who arrived on the Greek Islands – to the United Kingdom – where we opened a new project for asylum seekers in November – and from the Balkans to Libya, European migration policies have a severe impact on the lives of people seeking safety.

We treat refugees, migrants and asylum seekers who have been subject to inhumane migration policies. From the Aegean – where we provide care to people who arrived on the Greek Islands – to the United Kingdom – where we opened a new project for asylum seekers in November – and from the Balkans to Libya, European migration policies have a severe impact on the lives of people seeking safety.

Meanwhile, the situation has not improved for the nearly 800,000 Rohingya who fled to Bangladesh from Myanmar in 2017. We continue to run a range of medical services for Rohingya refugees, who still live in overcrowded camps and face increasing hostility from the government and local communities. In addition, global funding cuts to aid – upon which they rely to survive – have reduced the amount of food distributed and driven up demand for our services.

Challenges and triumphs in treating diseases

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, we have witnessed a rise in disease outbreaks, partly due to the severe toll it took on health systems and routine vaccination campaigns. In 2023, we treated thousands of patients for vaccine-preventable diseases like measles, cholera and hepatitis. Our teams struggled to respond to an outbreak of diphtheria, a potentially deadly bacterial infection, which affected Guinea, Nigeria, Niger, and Chad, because of a global shortage of both vaccines and antitoxins used for treatment.

During the year, we responded to an alarming number of people with malnutrition. MSF teams responded to crises in Nigeria, Ethiopia, Angola, Yemen, DRC, Afghanistan and Burkina Faso. People become malnourished for various reasons: conflict, cutting off supplies or preventing farming, poor harvests, high food prices, or insufficient food assistance for displaced people.

However, there was good news regarding tuberculosis (TB) during the year. In November, we published the positive results of the endTB clinical trial, which identified three new, safe drug regimens for multidrug-resistant TB, that are more effective and reduce treatment time by up to two-thirds. Some of these drug regimens use bedaquiline, the price of which has been a barrier to scaling up treatment. Through the work of MSF’s Access Campaign, the manufacturer, Johnson & Johnson, dropped some of its secondary patents on the drug in September, allowing for affordable generic versions to be used in low- and middle-income countries. The same month, the Access Campaign’s pressure on Cepheid, which makes a diagnostic test system widely used in MSF projects and its parent company Danaher, paid off when they agreed to a 20 per cent price reduction for some tests, including for TB.

In December, following three years of strong advocacy efforts by MSF, the World Health Organization added noma to its list of neglected tropical diseases. Noma is an infectious but non-contagious bacterial disease affecting mostly children, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. It is both preventable and treatable, but without treatment, it kills 90 per cent of people. Being on the list should shine a spotlight on the disease, facilitating the integration of noma prevention and treatment activities into existing public health programmes, and encouraging the allocation of much-needed resources to help tackle it.

We wish to express our heartfelt thanks to the more than 69,000 MSF staff, who worked in over 70 countries in 2023 – often at great risk – to deliver medical care to people in need.