Two pioneers of Doctors Without Border (MSF) HIV programmes in Khayelitsha, Dr Eric Goemaere and nurse Nompumelelo Mantangana look back at the defining moments of the last 20 years stitching together the legacy of the project in delivering patient-centred care, very often against the odds.

In the beginning

Eric Goemaere:

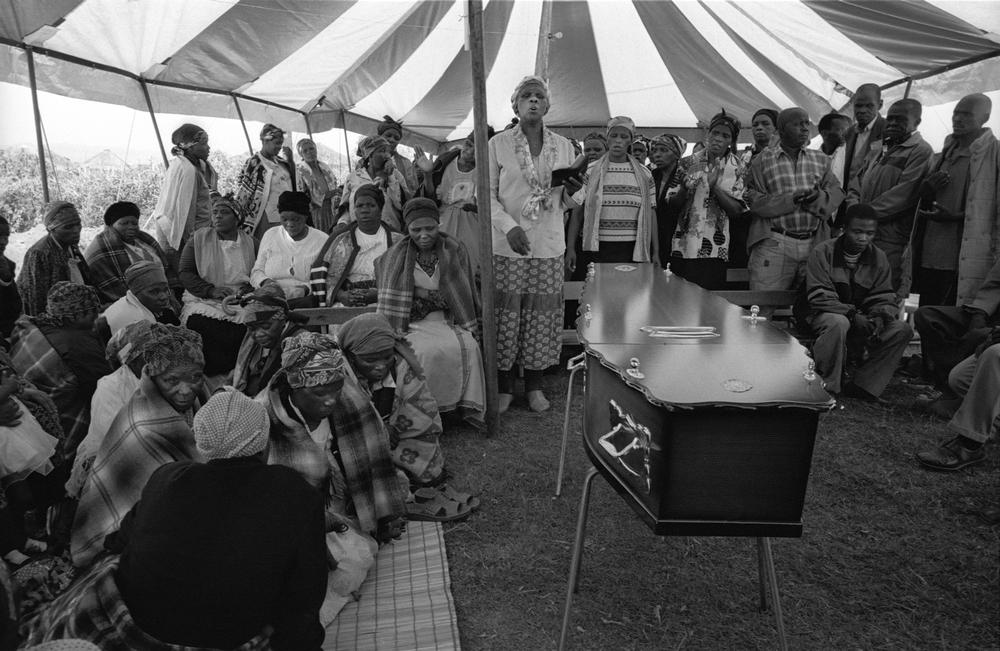

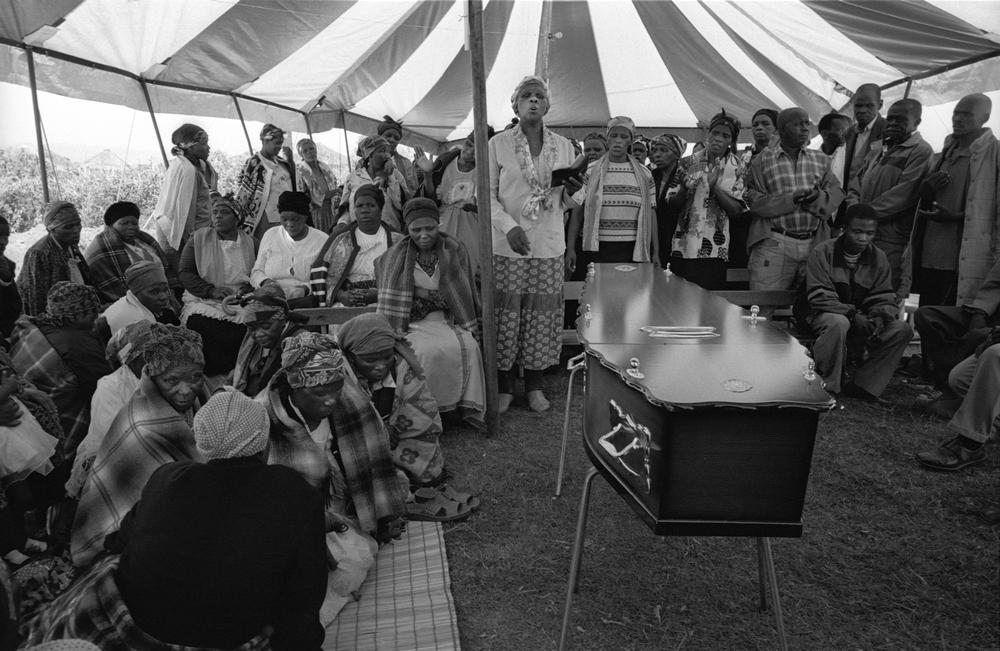

“MSF has been in Khayelitsha, and in South Africa, for 20 consecutive years, now responding to HIV and drug-resistant tuberculosis. It is difficult to compare today’s reality with the situation that we faced initially in 2000: 1,000 deaths per day from advanced HIV, cemeteries completely congested.

No treatment available in the public health system, and when you don't have treatment, you don't have a test, and when people don't want to test what you get is denial – and the carrier of this denial was the then president himself, Thabo Mbeki.

“Before I came to South Africa I had worked for MSF for many years. We first encountered HIV/AIDS in Central Africa. I remember we could not properly diagnose it, and needless to say, we couldn't treat it at all. But, in 1999 there was news of a simplified strategy to reduce transmission from HIV infected mothers to their unborn children out of Thailand making treatment feasible and affordable for resource-limited settings. Prevention of mother-to-child0-transmission (PMTCT) predicted reduced transmission rates by 50 % – by prescribing AZT, one of the first antiretrovirals.

“When I got to South Africa we initially planned to start a project in Alexandra in Johannesburg but shortly afterwards I learned that Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, the then Minister of Health, had already blocked the public-sector use of AZT and all antiretroviral treatment even to reduce mother-to-child transmission.

“Totally defeated I was preparing to leave the country. I phoned Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) co-founder Zackie Achmat to let him know. He was quite blunt and said, ‘Eric you don't understand anything about South African politics. Take a plane to Cape Town and I will explain how to deal with the politicians, plus I will introduce you to a place where you will certainly find something to do.’

“So I changed my plan and arrived in Cape Town.”

The Western Cape’s provincial health department and University of Cape Town (UCT) had initiated a PMCT programme in Khayelitsha and Goemaere negotiated MSF’s involvement.

“I asked if MSF could support and after some weeks of negotiations, Dr Fareed Abdullah agreed. Fareed was a former ANC activist who was head of the AIDS Programme in the Western Cape at the time. He told me ‘Eric, you can proceed with - let’s call it a trial – if you keep it discreet.’ Naturally, he was risking his job, and if I’m not mistaken he ultimately paid the price – a true hero of the HIV fight.”

Nompumelelo Mantangana:

“I started with MSF in those very early years, working in Ubuntu Clinic, the first of the three clinics MSF opened and ultimately handed over to local health authorities. At the time, the department of health did not want MSF to use AZT and used to order searches, so we used to hide the AZT in the boot of Dr Francoise Louis’ car. She was one of the first MSF doctors to work in Khayelitsha, along with Dr Hermann Reuter.

“To run the clinics they relied quite heavily on Xhosa-speaking nurses like myself, Victoria Dubula and Veliswa Labatala. We were more than nurses. We were activists who participated in establishing TAC branches in Khayelitsha.

Personally, I was activated by the experience of seeing my brother living with HIV. One thing that bothered us all at the start was the fact that we could not provide ARVs for the mothers – it was all very well to save the children, but we were creating a whole generation of orphans.

“It was our aim to offer triple therapy in our clinics but it was a financial impossibility – even the PMTCT programme was barely affordable. We were so desperate to treat patients that MSF and TAC staff actually smuggled ARVs into the country, but this was not a sustainable solution – ultimately, for an adult HIV programme to be successful the price of ARVs would need to drastically fall.”

The situation finally came to a head in 2001 after the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’ Association (PMA), a group representing 39 pharmaceutical corporations, sued the South African government. The PMA claimed an act that allowed the health minister to cancel patent rights to essential drugs, or import generic versions, in order to make low-cost medicines available to people who needed them contradicted the country’s constitution and a new international agreement on intellectual property rights by the World Trade Organisation. MSF, TAC and hundreds of thousands of supporters around the world united in the fight against this and the PMA formally dropped the case.

Of t-shirts and barrier-breaking treatment innovations

Eric Goemaere:

“The inexplicable stance of the South African government on HIV treatment remained a major challenge, and we operated with the sword of Damocles over our necks. As tensions mounted, TAC and COSATU and the local government played a major protective role but the threat to ongoing operations remained.

“Zackie called one day in early 2002 asking if I wanted to meet former president Nelson Mandela. The next morning I was at his house explaining what MSF had started in Khayelitsha to Madiba – basically begging him to come and rescue us. He agreed and a month later arrived at Site C Clinic in Khayelitsha. Naturally, we wished to capitalize on this show of support. We came up with this idea of presenting him with an “HIV POSITIVE” t-shirt, hoping that the media would record the moment. On the day, Matthew Damane, one of our first patients, presented the t-shirt to Madiba. To everyone’s surprise, he took off his own shirt and put on the “HIV POSITIVE” t-shirt. He was saying in front of everyone and in a very clear-cut way: treat HIV, it is unacceptable that so many people are dying. It was the peak of the defiance campaign, and it did more to change the perception of HIV than we could have hoped.

“From that moment we started to have much more support, including from the national department of health.

Nompumelelo Mantangana:

“One of MSF’s innovations of which I am personally proudest took place in Ubuntu clinic, where the HIV and TB services used to be housed in two separate shipping containers, completely unaligned – despite the fact that the HIV/TB co-infection rate was around 70%.

“We broke down the walls between the two containers and started work on the first-ever integrated HIV/TB programme, something which is now replicated around the world.

“In fact, so many of the differentiated models of HIV and drug-resistant TB care used worldwide were developed by MSF in Khayelitsha and proven at Ubuntu Clinic.

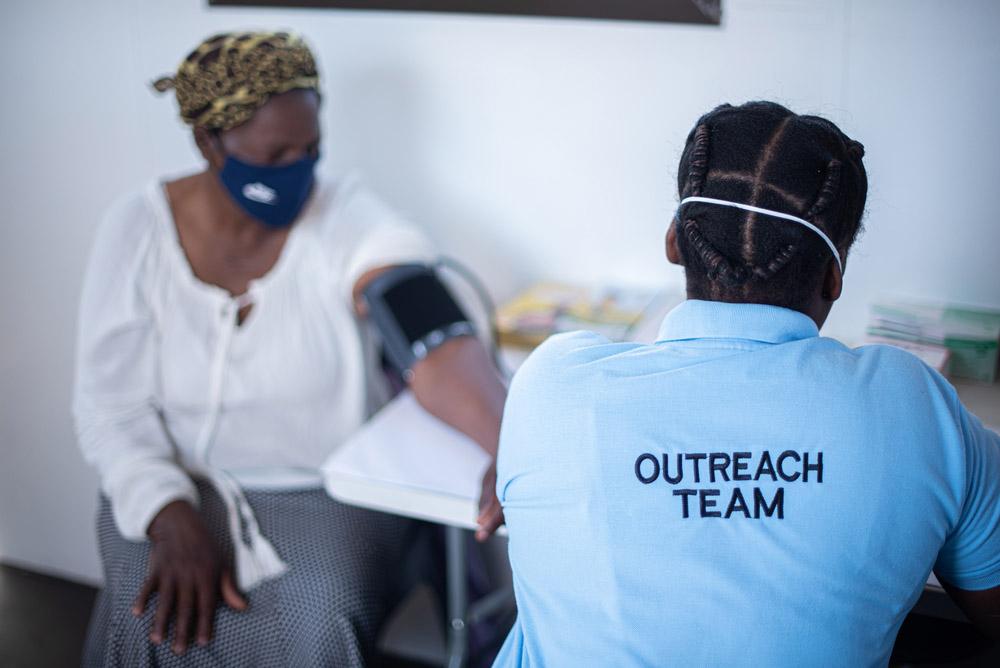

This included the first-ever ARV Adherence Clubs, which kept stable patients on ARVs by delivering efficient services in an environment of peer support. We could explain and discuss new developments in HIV care and get feedback from patients. It gave MSF the insight required to continue to develop ever-more patient-friendly interventions.

“Ubuntu became a sort of mecca for anyone wanting to find out more about HIV care feasibility in such destitute environment, including Bill Gates, Bono and Barack Obama. In 2009, UNAIDS executive director Michel Sidibé chose to give his inaugural address there.

Eric Goemaere:

“Our first office was located by the Site B taxi rank – TAC had an office next door. Today, MSF has an office in the Isivivana Centre, opposite the Khayelitsha District Hospital, which made it possible for MSF and the department of health to develop a successful COVID-19 field hospital in a little over a month earlier this year. When you walk into the office, you pass a wall of t-shirts, each one produced to mark a campaign, a protest, or the launch of an intervention.

“We jokingly refer to an epidemic of t-shirts. They neatly tell the story of MSF and the HIV response. At the start is a shirt bearing the words, ‘hamba kahle’, meaning farewell – farewell to all the people who died from HIV, 1,000 people a day at the time.

Then there’s a t-shirt celebrating the first dozen people on treatment, then years later another celebrating 20,000 on treatment. Today, there are around 42,000 people on ARVs in Khayelitsha. At the end of the line, for now, is a t-shirt bearing the words ‘Welcome Service’, referencing our current challenge to welcoming people who have stopped taking their ARVs back into care.

The major problem today is treatment fatigue – people stopping their ARVs, and then being too afraid to be stigmatized when returning to their clinic.

“South Africa has the largest ARV programme in the world, yet tens of thousands still die from AIDS-related illnesses every year. For people living with HIV, especially for people who have been on ARVs for 20 years now, we need new technology, including injectable ARVs or implants that could be p be reloaded every six to nine months, so that you don't need to come to queue in a clinic every month. Commitment to the improvement of HIV/TB care cannot waiver.”