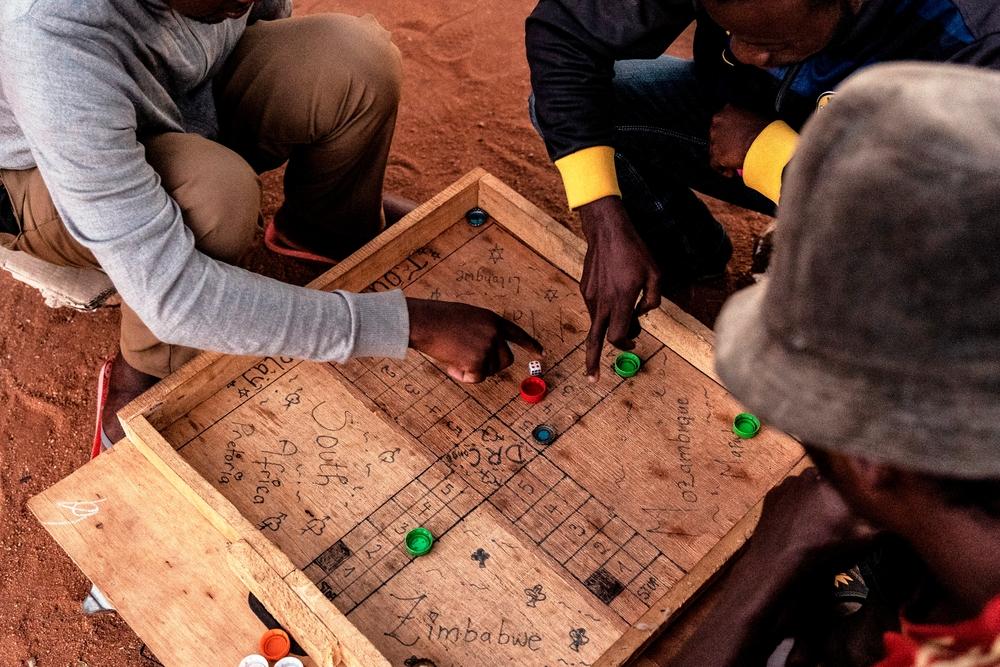

Beitbridge town has the busiest border post in Zimbabwe and the gateway into South Africa for thousands.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic some 15,000 people, including migrants and refugees from Zimbabwe and other countries, truck drivers and travellers, crossed the border from Beitbridge daily through either the official border post or illegal crossing points. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, that number has decreased to around 800, but migration has not stopped. Some people passing through Beitbridge seek asylum and apply for refugee status in South Africa.

Some people travel back and forth between South Africa and their place of origin or relocate entirely in search of a better life. In both cases, people passing through Beitbridge experience many hardships during their journeys - threats, violence, xenophobia, stigma, lack of food and water and limited access to health care.

Doctors Without Borders (MSF) teams provide medical assistance to people on the move passing through Beitbridge town and its surroundings. On World Refugee Day, we asked MSF Project Coordinator for the Beitbridge Mogration Project, Rinako Uenishi, to describe the current situation in and around this transit point.

Who uses the Beitbridge border post?

Many groups of people make use of the border post to get into and out of South Africa - migrants, including irregular ones, day passers, truckers, commodity buyers and sellers, people seeking medical attention and scholars, as well as refugees and asylum seekers. These groups are mainly from southern African countries or the other parts of Africa. Small minorities are even from Asia.

Who is a refugee?

A refugee is a person who has fled their own country because they are at risk of serious human rights violations and persecution there. The risks to their safety and life were so great that they felt they had no choice but to leave and seek safety outside their country because their own government cannot or will not protect them from those dangers. Refugees have a right to international protection.

Who is an asylum-seeker?

An asylum-seeker is a person who has left their country and is seeking protection from persecution and serious human rights violations in another country, but who hasn’t yet been legally recognized as a refugee and is waiting to receive a decision on their asylum claim. Seeking asylum is a human right. This means everyone should be allowed to enter another country to seek asylum.

Who is a migrant?

There is no internationally accepted legal definition of a migrant. Generally speaking, migrants are people staying outside their country of origin, who are not asylum-seekers or refugees. Some migrants leave their country because they want to work, study or join a family, for example. Others feel they must leave because of poverty, political unrest, gang violence, natural disasters or other serious circumstances that exist there.

Lots of people don’t fit the legal definition of a refugee but could nevertheless be in danger if they went home. It is important to understand that, just because migrants do not flee persecution, they are still entitled to have all their human rights protected and respected, regardless of the status they have in the country they moved to. Migration is a human condition undertaken in order to seek stable life.

Why are people leaving Zimbabwe?

In Africa, there are countries where people suffer from ongoing armed conflicts, economic recession and poverty – we call these “push factors”. In the case of Zimbabwe, push factors include:

- General protracted deterioration of the country’s economy and political stability, including a devalued local currency – which desperately lowers public servants’ wages and what they can purchase with it; and

- Lack of opportunities in the economy and high poverty levels, such that many people do not see any positive future prospects if they remain in the country.

- Lack of access to basic services such as healthcare, housing, education, water and sanitation, and other essential resources.

Why do people head to South Africa in particular?

South Africa is one of the economic giants in Africa – with a relatively high number of job opportunities (at least more than other neighbouring countries). Though crime remains prevalent in South African cities, there is no armed conflict or war – which is attractive to many people fleeing from violence elsewhere in the continent. Additionally, South Africa, unlike other Southern African countries, opted through its 1998 Refugee Act for an asylum policy which is characterised by non-encampment of asylum-seekers, freedom of movement, and the right to work and study.

In addition, its constitution sets out a number of rights to everyone in the territory, regardless of their immigration status, including access to public health care and education. However, in reality, the way policies are implemented within the framework of the law is different from how it was intended. Despite their hopes of having better lives in South Africa, many migrants and refugees may experience quite difficult lives there.

Why do people on the move need assistance?

Migrants often experience unpleasant events – discriminations due to their places of origin (including when accessing government services such as healthcare) and undignified treatment in detention centres or abuse when encountering police. Migrants traveling by road are particularly vulnerable. Due to poverty, they often choose more risky routes, where they face the dangers of violence and other traumatic events, accidents, lack of food and water, and limited access to healthcare.

In 2020, MSF conducted a survey around Beitbridge, interviewing 1,375 migrants in five different locations. Half of the interviewees said they experienced some kind of discrimination in South Africa, and 37% had suffered at least one episode of physical assault in the country.

Migrants who are deported from South Africa face additional challenges during the deportation process. In the 2020 survey, deportees who were interviewed noted poor living conditions and lack of access to healthcare services in police stations, where they were often held for protracted periods. Reports on human rights violations in police stations have previously been published by the South African Human Rights Commission, Human Rights Watch and Lawyers for Human Rights.

Sexual assault, exploitation and trafficking is also a problem for migrants and deportees -- 8.3% of survey interviewees reported they had sex in exchange for money or other goods and 16.7% admitted to having had sexual relationships against their will.

1,375

1,375

50 %

5%

37 %

37%

How has COVID-19 affected migration as experienced in Beitbridge?

Currently, South Africa is experiencing a “third wave” surge in COVID-19 infections. Like many other countries, South Africa’s economy has been affected by this pandemic. Many people lost their jobs – both South African citizens and migrants –and the official unemployment rate stands at 32.6%. On top of the hardships migrants already face, their lives have become even more difficult due to the pandemic and many are opting to return to their countries of origin.

According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), about 230,000 people have decided to leave the country in recent months and more returns are expected. In Beitbridge, we have been observing more and more people going back. This increased movement has also put additional strain on infection control programmes in Beitbridge and the Zimbabwe public health system.

What does MSF do in Beitbridge?

MSF is providing clinical (outpatient) and medical services to the migrant and refugee population. We are distributing hygiene kits and other commodities and supporting the Ministry of Health and Child Care with COVID-19 interventions.

Some of the services we offer include treatment for minor aliments; prescription refills of drugs for HIV, hypertension, diabetes, and asthma; sexual reproductive health services such as antenatal care and family planning; psychological first aid; HIV testing; and screening for tuberculosis.

We are also supporting a clinic in the town of Beitbridge, which is often utilized by migrants. MSF nurses provide support at the outpatient department, and we also use this clinic as a referral point from the migrant reception centre when lab tests need to be done or patients need further management.

How are you ensuring reduced transmission of COVID-19?

Infection control at the border is one of the crucial strategies to reduce transmission of the disease between countries. However, proper screening/testing and isolation of the cases is quite challenging for a resource-limited country like Zimbabwe.

For a land border like Beitbridge, the return or entry of people is unpredictable and the infection control systems in place can become overwhelmed. Insufficient lab machines and commodities may delay test results, and people awaiting results end up converging in places where it isn’t possible to properly observe physical distancing.

Recently, MSF has started an intervention focused on improving infection prevention and water and sanitation services in the area, which is crucial for minimizing the spread of the virus. MSF provides technical and hands-on support to improve the flow of people, promote handwashing and physical distancing practices and improve access to sufficient water supply and adequate sanitation.

How is MSF helping to reduce transmission of COVID-19 at illegal crossing points?

Along Limpopo river which forms the border between Zimbabwe and South Africa, there are some 10 unofficial crossing points where people travel to/from South Africa. These points are often used by people who do not have valid travel documents or work permits. We go to those points to provide medical services and raise awareness about handwashing and physical distancing.

There is also another key migrant hot spot called “Magogo’s house” – a house of an old Malawian lady where many Malawian migrants pass by before traveling to South Africa. There, we are providing medical and psychosocial support over and above COVID-19 services.

What kind of changes would improve the health of people on the move in Southern Africa, from your perspective in Beitbridge?

Southern Africa will remain a vibrant region with many people on the move within, into and out of cities and countryside of the region. These people should be guaranteed access to healthcare. Our project has designed models of care to meet the health needs of people travelling to and from South Africa. We are also calling for additional improvement in the following areas:

- A shorter transit and asylum processes from South African authorities, as some people stay as much as nine to 12 months in Musina, the town adjacent to Beitbridge on the South African side, waiting for their applications to be processed. During this period, the limited health services available in Musina are increasingly strained and at times unable to cope with especially high numbers of incoming migrants (as well as domestic residents). Shelters that are available are not well-equipped to support these needs, despite their important efforts. Further, those experiencing acute mental health or physical conditions would not be able to access care in Musina. During the COVID-19 pandemic, large numbers of individuals with nowhere to go to, and who are stuck in Musina, may exacerbate the risk of community transmission of infection.

- Improved infection control procedures and testing by officials before deporting people from South Africa;

- Improved infection control procedures and testing by officials before deporting people from South Africa;

- Access to treatment refills, preventative care such as condoms, family planning and feminine hygiene products, as well as PEP for those on the move

- Increasing access to vaccination for minors (EPI); improving links to emergency health services as well as maternal and child health services; primary healthcare for all as a way to enhance overall improved health for host and transiting populations; adapted care for different ethnicities (including translation support, where needed).

- Better treatment for migrants and refugees by government officials in healthcare, policing and immigration throughout their journey, as per international agreements on the treatment of migrants and refugees.