Barely a decade after gaining independence, the world’s youngest nation continues to face overlapping crises such as open conflict, violence, insecurity and limited access to healthcare. For nearly three years now, the war in neighbouring Sudan has unleashed yet another emergency, forcing hundreds of thousands of people to flee across the border to a country unprepared to absorb such an influx.

To document this crisis, we collaborated with Nicolò Filippo Rosso, an internationally renowned photographer recognised for his powerful and evocative documentary work. He travelled to meet those living close to the border between Sudan and South Sudan, a context largely overlooked by media attention.

“I've been observing the Sudanese conflict from the sidelines for some time now,” explains Nicolò. “I did several reportages in Eastern Chad, where I mainly encountered women and children fleeing the conflict in Sudan seeking refuge in overcrowded camps. In South Sudan, the crisis is quite different, I saw a total collapse of the health system and an extremely layered crisis both for Sudanese refugees and internally displaced people.”

An improvised escape route for people fleeing Sudan

After landing in Juba, the capital of South Sudan, and attending several briefings with MSF teams, Nicolo travelled to Abyei Special Administrative Area, a territory long disputed between Sudan and South Sudan. For years, it has been hosting internally displaced people fleeing violence in other states, but the outbreak of the war in Sudan has pushed the situation to a critical level.

What really struck me in Abyei was the number of injuries. I saw people with gunshot wounds and severe burns arriving at the hospital. I couldn’t help but wonder what was happening back home for those who stayed, and the conditions they were living in- Nicolò Filippo Rosso

As the war in Sudan pushes deeper into Darfur and the Kordofan states and has reached its 1,000th day with no sign of respite, Abyei has become an improvised escape route. Many civilians arrive by foot, not only from Sudan but also from other South Sudanese states affected by years of violence and displacement. These movements place immense pressure on health facilities that were never designed to cope with such a massive and sustained influx of displaced populations.

“I met a woman named Regina,” Nicolò recalls. “She was very sick with tuberculosis and feared she might die. She didn’t have the strength to carry her children with her to the hospital, so she left her children by the market under a tree with a few belongings and some food, asking someone she knew to watch over them. She went to get treatment with no phone, no connection, hoping that after several weeks she could return and find them. It was a heartbreaking story.”

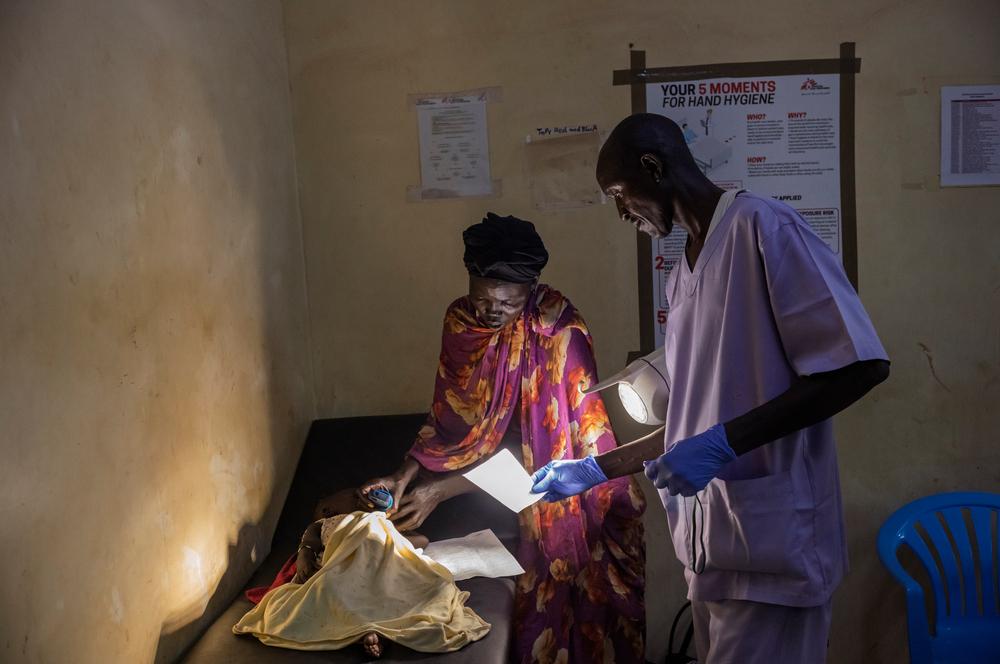

MSF’s Ameth Bek Hospital, the only functioning hospital care facility in the region, is increasingly overwhelmed by patients. The teams are focusing particularly on emergency services, including surgery, but also inpatient care and midwifery. Between January and September, MSF provided surgical care to 1,240 patients, including those with violence-related injuries.

It’s great to see MSF working because the impact is immediate and tangible. You can actually see change happening: someone is sick, and hours later you already see them recovering. Everything you document reflects that transformation.Nicolò Filippo Rosso

Meeting the needs of remote communities

In addition to running the hospital, MSF has nine i.e.9 integrated community case management (ICCM) sites managed by trained local volunteers in collaboration with local health authorities. MSF’s team travels long distances to the village health posts to bring medicine and support the trained community health workers.

“Some communities are really counting on the community health sites because they are extremely isolated,” explains Nicolò. “When they visit those sites, they can find trained staff and receive the care they need. It was the case of Ayom Deng, a young girl who suffered a serious burn injury while cooking at home. Her mother brought her to the community health site after seeing the wound worsen. Ayom received wound care and follow-up instructions as part of the program. It really brings essential healthcare closer to villages far from formal health facilities.”

Providing comprehensive care to uprooted families

After several days of documenting the situation in Abyei, Nicolò travelled further south, to Mayen-Abun. There, displacement has taken a different form but is no less urgent: families have been repeatedly forced to flee their homes by long-standing conflicts, including cattle raiding, land-use disputes, intercommunal violence, and climate-related crises. In the MSF-supported hospital, the teams focus on providing comprehensive care, from outpatient consultations to emergency and maternity care.

“I had the chance to accompany Abuk throughout her delivery, from the moment she was admitted until the birth of her baby,” shares Nicolò. “Births are always very emotional moments, and mothers are generally quite open to being accompanied by a camera. It was a very intimate moment, and I even got a high five after she made her final push.”

In rural communities outside Mayen-Abun, access to basic healthcare is also extremely limited. Clinics are few, distances between settlements are long, and many families must walk for hours to reach the nearest health post. As in Abyei, MSF works closely with communities. By bringing basic but essential care closer to where people live, these essential sites help bridge the gap created by the country’s collapsing health system and the insecurity that prevents families from reaching hospitals.

A fallen health system amid funding cuts and structural weakness.

All these difficulties are exacerbated by a wider crisis. Despite being the world’s youngest country, South Sudan remains heavily dependent on humanitarian aid: more than 80% of essential health services are run with the support of NGOs.

In July 2024, the Health Sector Transformation Project (HSTP) launched a multi-donor-funded initiative (including the World Bank) to support basic health and nutrition services and emergency preparedness in South Sudan. Led by the government and implemented in collaboration with the WHO, UNICEF, and implementing partners, the model initially planned to support 1,158 health facilities across 10 states and three administrative areas over three years. However, due to funding constraints, it will now support only 816 facilities until 2027, leaving significant gaps in coverage.

Now more than ever, it is clear that this model is deeply unsustainable: some organisations are forced to close their doors after massive cuts in international aid, and others because of insecurity and violent attacks, causing the entire health system to collapse. For patients receiving care from MSF, this is a painful reality: once they leave the facilities, there are few, if any, other places to turn for help and support.

Across all MSF project locations, teams are witnessing the devastating impact of a chronically under-resourced system. Many primary healthcare facilities are non-functional, essential medicines are frequently unavailable, staff salaries are delayed, and hospitals are neglected. As a result, people in need of lifesaving surgery or emergency maternal care have extremely limited options.

These pressures are unfolding alongside overlapping crises, including violence, mass displacement, flooding, and disease outbreaks, all of which further strain an already fragile system. In 2025 alone, MSF opened 12 emergency projects in response to cholera outbreaks, malaria peaks, flooding, and displacement linked to violence, more than double the number of emergency responses launched in 2024.