Response to conflict in eastern DRC

The conflict in North and South Kivu, which began in 2021, escalated in 2024 between the M23, the Congolese armed forces (AFC), their respective allies, and other armed groups, causing new waves of displacement. In February alone, 250,000 people arrived in the already overcrowded camps on the outskirts of Goma, the capital of North Kivu. In 2024, the living conditions in the camps continued to deteriorate, due to a lack of national and international action, and the frontlines moved closer to the city, making them more vulnerable to armed violence. Many civilians were caught in the crossfire, with numerous killed or wounded by heavy artillery shelling, while others were subjected to sexual violence.

To address this critical humanitarian crisis, we scaled up our emergency response efforts, strengthening general, maternal, and paediatric care, delivering lifesaving vaccinations, and providing treatment for victims and survivors of sexual violence, many of whom were women and children. In 2024, our teams treated an unprecedented number of people for sexual violence in North Kivu. We remained the primary water provider in the camps around Goma, making significant investments in sanitation infrastructure, including a solar-powered water supply system, a water-pumping station, and a faecal sludge treatment plant. These efforts were critical, as we also treated thousands of patients for cholera in the displacement sites.

Escalating fighting on multiple fronts and repeated forced displacements in both North and South Kivu further limited people’s access to healthcare, including vaccinations. As a result, there was a rise in cases of malnutrition, measles, and cholera in the hospitals and health centres where our teams work. Medical facilities where MSF teams are working have seen a significant influx of war-wounded patients and civilians seeking safety from ongoing fighting, particularly in the towns of Mweso and Masisi in North Kivu. To assist people on the move, our teams set up mobile clinics in displacement areas, although high insecurity repeatedly restricted our movements, particularly in Masisi territory.

In early 2024, in South Kivu, tens of thousands of people fled to Littoral and Hauts-Plateaux in the Minova health zone. This was followed by other massive movements later in the year, which brought the number of displaced people in the area to over 200,000. We launched emergency activities, delivering medical care to the sick and injured, and improving hygiene conditions in displacement camps, following an increase in cholera and measles cases.

The ongoing crisis in Ituri province has been largely overlooked by the DRC government, and has seen a limited international response, despite continued and widespread attacks on civilians throughout 2024. Neither hospitals nor sites for displaced people were spared. On 6 March, Drodro General Referral hospital was attacked and looted by armed individuals, who killed a patient in her bed. This, and other violations of international humanitarian law, had a significant impact on people’s access to healthcare in Ituri.

We continued to support Salama clinic in Bunia, providing surgery and post-surgical care, including physiotherapy, orthopaedic services, and mental health support for patients suffering from trauma or violence-related injuries. We also helped 13 health zones in the province to prepare for mass-casualty events by conducting training and strengthening the referral system.

MSF maintained support for the two general hospitals in Angumu and Drodro, as well as the surrounding displacement sites, focusing on treatment for malaria and respiratory infections, and maternal and paediatric care.

Response to disease outbreaks and other emergencies

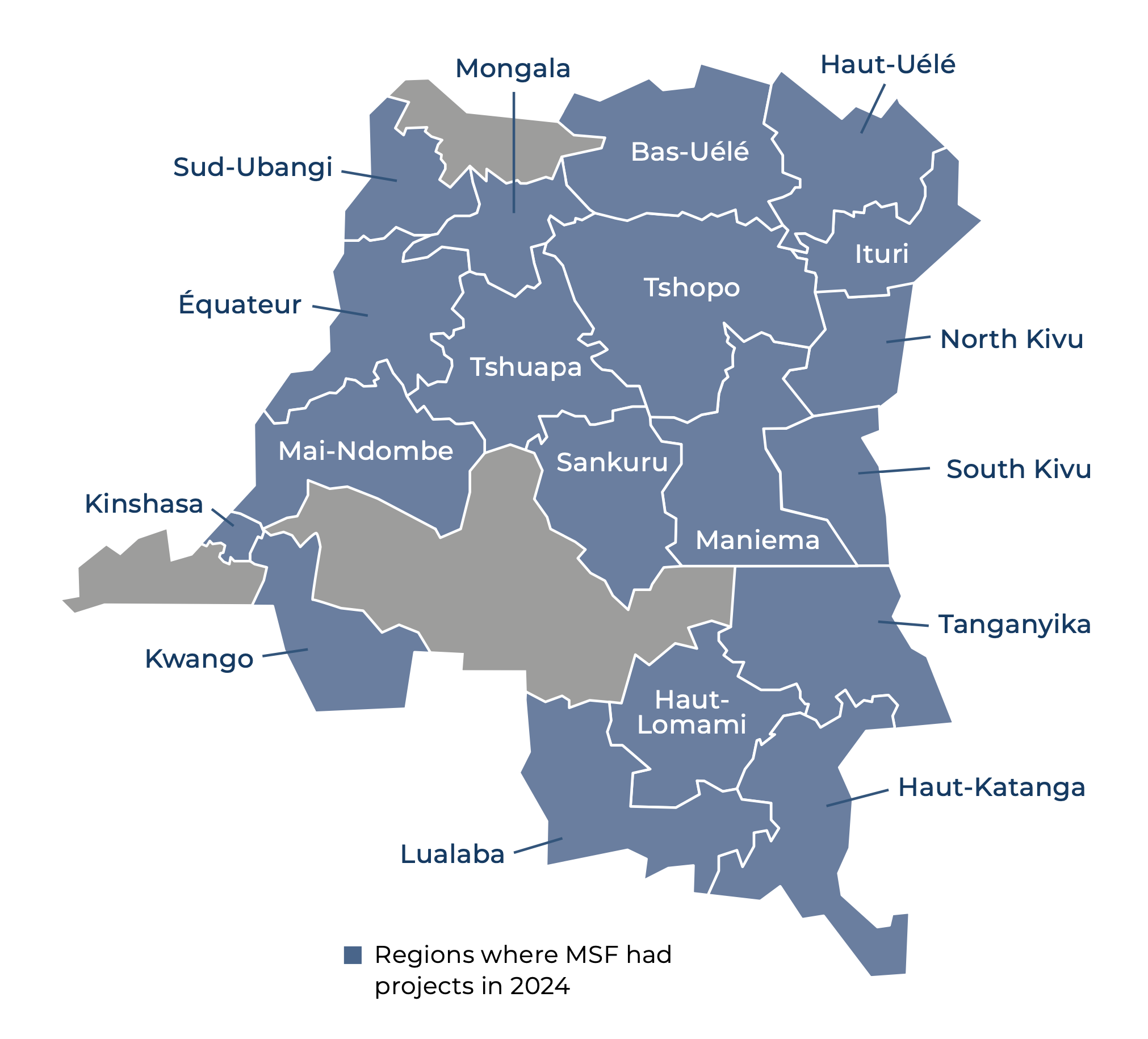

During the year, we ran emergency interventions to support people displaced by conflict or natural disasters in other regions of the country, including Mai-Ndombe and Kisangani.

While responding to measles epidemics remained a primary focus for MSF’s emergency mobile teams throughout 2024, we also addressed a surge in outbreaks of mpox, formerly known as monkeypox. The rise in cases was driven by a mutation that enhanced human-to-human transmission of the virus. This was compounded by extremely high population density in displacement sites around Goma, North Kivu, and Minova, South Kivu.

In Équateur, South Kivu, South-Ubangi, North-Ubangi, Tshopo, Haut-Uélé, Bas-Uélé, Ituri, and North Kivu provinces, we conducted epidemiological surveillance, awareness-raising, and research activities, and supported the Ministry of Health with patient care. In Tshopo, we also responded with surveillance and supported the Ministry of Health in setting up and running two treatment centres. In Uvira, a hotspot for mpox in South Kivu, MSF assisted with case management, infection prevention and control measures, and community awareness-raising.

In January, when torrential rains caused flooding in the capital, Kinshasa, our logistics teams worked to construct latrines and showers, and distribute drinking water and tents, while our medical teams provided medical and mental health care.

General and specialist care activities

Alongside our emergency activities, we continued to run our regular projects across DRC. These include supporting health facilities and training networks of community health workers to detect high-prevalence conditions such as malaria and malnutrition, particularly in hard-to-reach areas.

Care for victims and survivors of sexual violence is another major component of many of our projects. Our teams provide not only medical treatment, but also psychological support, and engage communities with awareness-raising activities to ensure that people know where to seek treatment.

In Kinshasa, we offer HIV care in Kabinda hospital and five health centres. In addition, we are working to improve access to healthcare for people with disabilities, such as by supporting health facilities in becoming wheelchair-accessible and sending mobile clinics with sign language interpreters to communities.